Key Points:

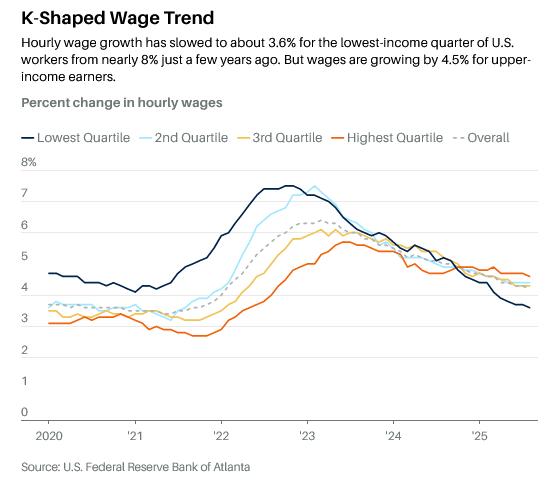

- Wages for the top 25% of the U.S. workforce are rising by 4.6% annually, while the lowest quarter sees only 3.6% annual gains.

- Financial stress is increasing for lower-income households, with 29% living paycheck to paycheck and a record 6.7% of subprime auto loans delinquent.

- The economy’s growth is increasingly reliant on affluent households, as lower-income consumers face rising costs and reduced spending capacity.

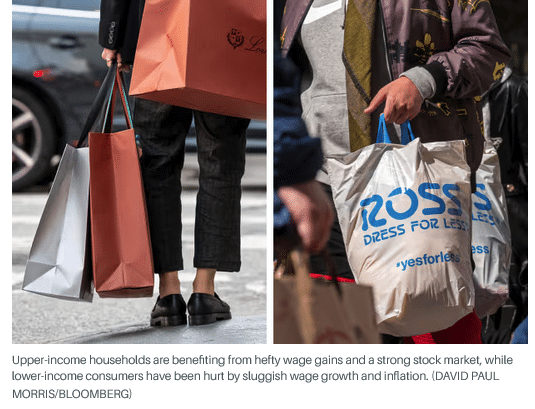

After years of narrowing wage inequality, the workplace has become a tale of two economies again. This time, unlike in the postpandemic period, trends favor the top 25% of the U.S. workforce, whose wages are rising by 4.6% a year. That compares with annual wage gains of only 3.6% a year for the lowest quarter of the workforce, or roughly half the pace in 2022, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

The reversal in fortunes has popularized the notion of a K-shaped economy, in which, like the letter, the upper arm rises while the lower arm droops. Fresh data about wages, spending, and credit conditions from banks, economists, and the Fed show the divergence widening this year. The U.S. economy is still expanding—gross domestic product is expected to grow by about 1.7% in 2025—but its health depends increasingly on more affluent households.

Bank of America data show that 29% of lower-income households are now living paycheck to paycheck, up from 27% in 2023. “Wages for lower-income earners have been easing relative to their higher-income counterparts since the beginning of 2025,” says Joe Wadford, a Bank of America economist.

Financial stress is also mounting among the less well off. Cox Automotive reported 1.7 million vehicle repossessions in 2024, up 43% from two years earlier and the highest level since 2009. This year is likely to be worse: The number of subprime borrowers at least 60 days behind on their auto loans rose to nearly 6.7% in October, the highest level on record, according to Fitch Ratings data.

TransUnion reports that more borrowers now cluster at credit score extremes: either superprime, with scores above 780, or subprime, below 600. “We are seeing a divergence in consumer credit risk, with more individuals moving toward either end of the credit-risk spectrum,” says Jason Laky, TransUnion’s executive vice president and head of financial services.

Mark Zandi, Moody’s chief economist, says spending among the bottom 80% of households, those earning less than $175,000, has kept pace with inflation since the pandemic. But the top 20% have done far better, and the wealthiest 3% “much, much, much better.”

Those high-income consumers are now powering growth. “As long as they keep spending, the economy should avoid recession,” Zandi wrote. “But if they turn more cautious, for whatever reason, the economy has a big problem.”

In a recent speech, Federal Reserve Governor Christopher Waller put more numbers around the growing imbalance. The top 10% of households account for 22% of all personal consumption, and the top 20% contribute 35%, he said in October citing Fed and Bureau of Labor Statistics data. The bottom 60% represent 45% of consumption. “This group has been affected by higher prices this year and is already changing its spending plans to find better value,” he said.

The K-shaped pattern changes the economy’s resilience. When wage gains cluster in the top income strata, growth becomes more sensitive to changes in the financial markets and less anchored to ordinary income.

Affluent households, which also control the greatest share of wealth, may keep spending, but their behavior is likely to swing with asset prices, exposing the economic expansion to greater volatility. According to Jared Bernstein, chair of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Joe Biden, the decline of a dollar in stock market wealth translates to two to three cents less in spending.

An increasingly unbalanced economy also changes the way economic weakness is reflected in data. Growing stress among lower-income households manifests in rising delinquency rates, shrinking buffers, and reductions in discretionary spending, which then hurt businesses that depend on widespread demand rather than high-margin customers. While the economy can continue to grow for some time while its foundations erode, policymakers are left with a clouded picture of its underlying condition.

Inflation is a particular drag for lower-income households, even if headline inflation has fallen to 3% or so from a high of around 9% in June 2022, as measured by the consumer price index. Joe Brusuelas, an economist at RSM, notes that shelter costs have risen 3.6% over the past year, utilities 5.8%, and beef nearly 15%.

Bank of America has found that inflation is outpacing after-tax wage growth for both middle- and lower-income earners. Tariffs are compounding the problem: Yale’s Budget Lab estimates an average effective tariff rate of 17.9%, the highest since 1934, which has lifted prices about 1.3% and cost the typical household $1,800 so far.

Federal Reserve officials have begun to speak more openly about the K-shaped economy, even if they don’t invoke the alphabet to describe it. Philadelphia Fed President Anna Paulson has said that nearly all net job growth this year has come from healthcare and social assistance. With lower-income consumers under strain, she warned, the economy is increasingly reliant on spending by affluent consumers, much of it tied to a narrow stock market rally driven by AI-linked companies.

“The relatively narrow base of support for the labor market, the importance of high-income consumers, together with the prominence of the narrative around AI for equities, adds up to a relatively narrow base of support for growth,” Paulson said. “Indeed, some business contacts are wondering where future demand will come from. This is something to watch closely.”

Fed Chair Jerome Powell has also expressed worries. “If you listen to the earnings calls or the reports of big, public consumer-facing companies, many of them are saying that there’s a bifurcated economy,” Powell said after last month’s Fed policy meeting. “Consumers at the lower end are struggling and buying less and shifting to lower-cost products. But at the top, people are spending.”

Business leaders are taking note. “We continue to see a bifurcated consumer base,” said McDonald’s CEO Christopher Kempczinski on the company’s most recent earnings call.

Traffic from lower-income consumers declined by nearly double digits in the third quarter, he said, “a trend that’s persisted for nearly two years.” Traffic growth among higher-income consumers, in contrast, “remained strong, increasing nearly double digits in the quarter,” he said.

Henrique Braun, chief operating officer of Coca-Cola, said on a recent analyst call that the company had leaned into “mini-cans” to appeal to cash-strapped consumers. “When we look from a consumer point of view, we continue to see divergency in spending between the income groups,” he said. “The pressure on middle- and low-end income consumers is still there.”

The bifurcation creates policy challenges for the Fed, which faces conflicting signals. The softening labor market argues for continued rate cuts to prevent further deterioration, while inflation that has run consistently above the central bank’s 2% annual target for the past five years argues for caution.

The Fed’s tool kit isn’t designed to address distributional problems. It can try to support the labor market broadly, but it can’t target specific wage groups. It can ease financial conditions, but that primarily benefits asset owners.

Brusuelas described September’s CPI report, which showed prices rising by a less-than-expected 3% on an annual basis, as “the perfect depiction of the K-shaped economy.”

Beneath the headline numbers, he said, “middle-class and down-market households experiencing slowing wage growth are having difficulty adjusting to persisting increases in the cost of living. For those households, it is about food, fuel, and utilities.”

Households exposed to assets will continue to prosper as rate cuts bolster equity prices, he wrote. Upper-income households with rising incomes and appreciating assets can capitalize on current conditions. “The upper spur of the Big K is a good place to be,” he wrote.

But the “Big K” itself is a troubling look for the broader U.S. economy.

Read the full article HERE.