Officials are hoping to prevent a gradual cooling in the labor market from turning into a deeper freeze

The Federal Reserve voted to lower interest rates by a half percentage point, opting for a bolder start in making its first reduction since 2020. The long-anticipated pivot followed an all-out fight against inflation the central bank launched two years ago.

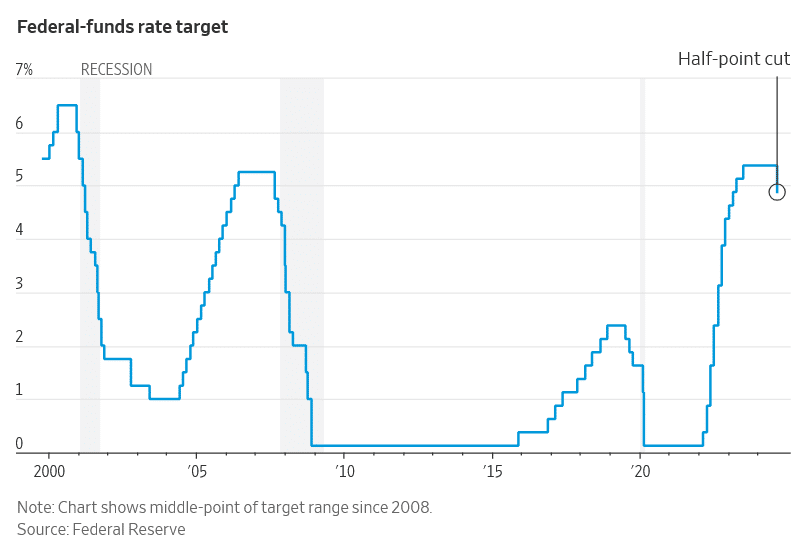

Eleven of 12 Fed voters backed the cut, which will bring the benchmark federal-funds rate to a range between 4.75% and 5%. Quarterly projections released Wednesday showed a narrow majority of officials penciled in cuts that would lower rates by at least a quarter point each at meetings in November and December.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s decision to trim rates by a larger amount than most analysts anticipated until just a few days ago moved the central bank unwaveringly into a new phase of its inflation battle: It is now trying to prevent past rate increases, which last year took borrowing costs to a two-decade high, from further weakening the U.S. labor market.

“We are committed to maintaining our economy’s strength,” Powell said at a news conference. “This decision reflects our growing confidence that with an appropriate recalibration of our policy stance, strength in the labor market can be maintained.”

In its policy statement, the Fed said the decision reflected “greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2%” and that the central bank “judges that the risks to achieving its employment and inflation goals are roughly in balance,” the Fed said in its policy statement Wednesday.

Stocks rose after the Fed announcement. Anticipation of rate cuts buoyed Wall Street in the run-up to this week’s meeting, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average hitting a new record on Monday. Yields on the 10-year Treasury note stood at 3.64% on Tuesday, ticking up slightly from a 52-week low recorded on Monday.

The decrease should provide some immediate relief to consumers with credit card balances and to small businesses with variable-rate debt. Long-term borrowing costs—on everything from mortgages to corporate debt—have already been declining in anticipation of a series of rate cuts this fall, particularly after Powell last month said reductions were on the way.

A rate cut never appeared to be in doubt this week, but analysts were uncharacteristically foggy over the size of the move. Many anticipated a smaller quarter-point cut. Fed officials have often preferred to make smaller changes in order to avoid having to reverse course if their moves prove premature.

Powell’s apparent decision to push his colleagues to make a half-point cut likely reflected so-called risk management concerns in which officials weigh the risks of various economic hazards, such as high inflation or rising joblessness, and navigate accordingly

For most of the past 2½ years, as inflation hit 7%, Powell had been single-mindedly focused on preventing inflation from becoming entrenched. Central bankers have long been haunted by the example of the 1970s, in which they took insufficient steps to constrain demand and allowed expectations of higher prices to become self-fulfilling.

But inflation has fallen over the last year, assisted by healed supply chains and a steady influx of workers to the job market. That suggests the downturn many economists once thought might be needed to tame inflation would now be overkill.

Meantime, more signs that the job market is softening have cropped up. The unemployment rate stood at 4.2% last month, up from 3.7% in January. Powell last month signaled he was shifting the Fed’s attention to preventing what for now looks like a gentle cooling in labor demand from turning into a deeper freeze.

In their projections, all Fed officials thought the unemployment rate would end the year between 4.2% and 4.5%. In June, most saw the unemployment rate settling around 4.0% at year-end.

While some Fed officials had argued in recent weeks the economy wasn’t weak enough to necessitate a half-point cut, others had concluded that labor-market cooling this summer warranted a larger reduction because the Fed was, in effect, catching up for lost time.

Fed officials entertained but opted against cutting interest rates at their previous meeting at the end of July. Two days later, hiring figures showed a sharper-than-expected slowdown in payroll growth and a bigger jump in unemployment. While central bankers don’t get mulligans, they might have opted for a cut if that data had been in front of them at the July meeting. A larger cut this week offered the chance to reset.

Some officials also feel greater urgency to cut rates because they are increasingly confident that rates are well above a so-called neutral level that neither spurs nor slows growth, and that rates will continue to be at a restrictive level even after Wednesday’s cut. With the economy closer to a healthy equilibrium, keeping conditions there could call for moving rates closer to this neutral level, which can’t be observed.

Fed governor Michelle Bowman dissented against Wednesday’s decision in favor of a smaller quarter-point cut. Bowman, who was appointed to the board by Donald Trump in 2018, became the first governor to dissent against an interest-rate decision since 2005. It was the first dissent by any voter on the rate-setting committee since June 2022.

The Fed rate cut marks just the sixth time in the past 30 years that the central bank switched from raising to lowering rates. Usually when the Fed starts cutting rates, it doesn’t know whether it will make a handful of small moves—as it did in 1995 and 1998 when the economy avoided a downturn—or whether it is the start of a longer series of reductions, as in 2001 and 2007 when the central bank cut rates a few months before the economy entered recession.

Interest-rate projections show officials penciled in the equivalent of another four cuts of a quarter point next year, assuming the unemployment rate doesn’t jump and inflation continues to decline. That would take the fed-funds rate to just below 3.5% by the end of 2025.

Officials are walking a fine balance as they attempt to engineer a soft landing that brings inflation down without a recession, all while trying to tune out crossfire from politicians ahead of the fall elections.

Three Senate Democrats, including Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, called on Powell this week to make a larger cut of 0.75 point, something the Fed has only done when the economy is in obvious distress.

Some Republicans are upset that a rate cut might boost sentiment ahead of the November election. The rate cut is a sign the economy is “not good. Otherwise you wouldn’t be able to do it,” Trump said at a town hall on Tuesday night. Powell has said the Fed doesn’t take political considerations into account.

Rep. Patrick McHenry (R., N.C.), who chairs the House Financial Services Committee, said in an interview Tuesday he expected the Fed to ignore political noise. “The Fed should act in the way that the data indicates they should act—period,” he said. “The outrage to me is … for instance, if you’re on the right, you say, ‘The Fed should be independent, except I think right now they should do this.’ And on the left, the same.”

The Fed slashed rates to near zero in March 2020 as the Covid-19 pandemic brought global commerce to a standstill, and officials held rates at that level for two years. In the spring of 2021, they misdiagnosed a sharp rise in inflation as likely to be short lived.

Powell pivoted at the end of 2021, first withdrawing stimulus and then lifting rates in March 2022. Inflation hit 40-year highs, and officials quickly reeled off hikes in unusual 0.5- and 0.75- point increments. It was the most rapid interval of rate increases since the early 1980s, and it took rates to a two-decade high in July 2023.

Most global central banks reacted in a similar fashion to inflation that soared in most of the world’s advanced economies, first as economies reopened from the pandemic and later as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine drove up energy and commodity prices. With Wednesday’s rate cut, the Fed joins policymakers in Canada, the European Union, and the United Kingdom, among others, in beginning to dial down interest rates.

Powell signaled at the end of last year that the Fed was probably done raising rates and was turning its attention to when to cut, but officials scrapped tentative plans to begin reducing rates this summer after a sharper-than-expected burst of inflation greeted the U.S. economy in the first quarter.

At their meeting in June, a narrow majority of officials thought the Fed would make just one quarter-point cut this year, and some officials this spring puzzled over why higher borrowing costs hadn’t done more to slow economic activity.

But in recent months, the fingerprints of tighter monetary policy have become more apparent, convincing officials they could finally ease off the brake pedal. While layoffs are low, hiring has slowed. There were fewer than 1.1 job vacancies for every worker counted as unemployed in July, down from 1.25 before the pandemic and from a peak of 2 when the Fed began raising rates in March 2022.

Interest-sensitive manufacturing and real estate sectors have been soft. Corporate America has increasingly warned that low- and middle-income consumers are resisting higher prices, leading to more promotions and discounts.

Inflation receded to 2.5% in July from around 5.5% in January 2023. Wage growth has slowed in recent months, and oil prices are down 19% since April.

Economists are also divided over whether rate cuts will help avert a sharper slowdown in the months ahead. Unlike 2001 and 2007, when the Fed initiated rate cuts with a larger half-point reduction, the economy isn’t suffering from evident financial-market stress or deflating asset bubbles.

On the other hand, modest rate cuts might be of little help to corporate borrowers who locked in much lower fixed borrowing costs before 2022 and who need to refinance over the next year at rates that could still be high, even as the Fed dials rates down.

It’s also unclear how much marginal declines in rates will stoke housing activity given serious affordability challenges. While mortgage rates have fallen meaningfully in recent weeks, there haven’t yet been notable signs of increased demand. Applications for home purchase loans last week were no higher than their level one year ago, even though mortgage rates are down sharply. Rates fell to 6.2% last week, the lowest level in more than a year and a half.

Just as Fed officials and private-sector economists misjudged how the transmission of higher rates to the economy two years ago had been dulled by households and businesses that locked in low rates, “there’s a risk the easing cycle will see some similar challenges,” said Rebecca Patterson, former chief investment strategist at Bridgewater Associates.

Bond investors are anticipating another 2 percentage points in rate cuts over the next 1½ years, while stock valuations suggest investors see healthy earnings growth over the next year. “For all of that to transpire, you need to see Fed easing have that supporting effect on consumer and business activity,” said Patterson. “The channels can’t get clogged.”

See full article HERE