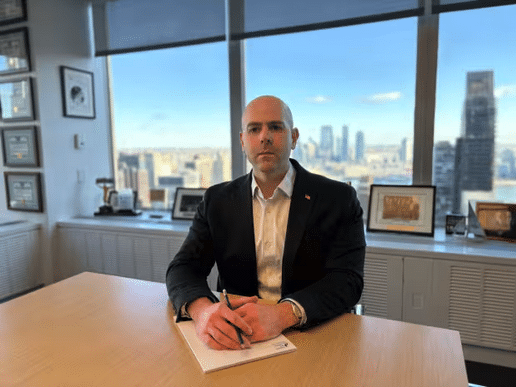

Stephen Miran, nominated to advise Trump, has suggested high tariffs could be the price allies pay for U.S.’s defense umbrella

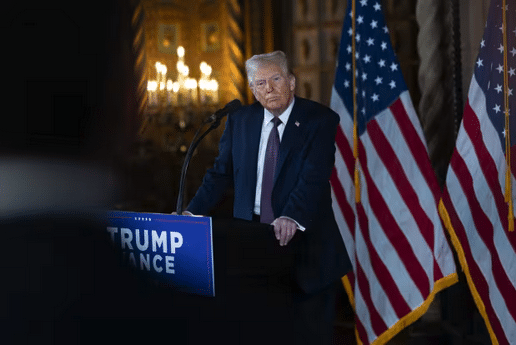

To serve as an economic adviser to Donald Trump, it helps to share his belief that tariffs make the U.S. richer. Not many economists meet that criterion.

Stephen Miran has made just that case. Miran, the president-elect’s choice to chair his Council of Economic Advisers, has written that the U.S. could be better off with average tariffs of around 20% and as high as 50%, compared with the current 2%.

Miran’s views are worth studying, and not just because he’s going to advise Trump. He has described tariffs as a tool, and international intervention to weaken the dollar as another, that could address a longstanding global tension: the U.S.’s economic and military support for other countries have contributed to an overvalued dollar, wide trade deficit and hollowed-out industrial base.

“Sweeping tariffs and a shift away from strong dollar policy can have some of the broadest ramifications of any policies in decades, fundamentally reshaping the global trade and financial systems,” Miran wrote in a November report for Hudson Bay Capital, where he is senior strategist.

Miran wrote the report “A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System” before he was named in late December as Trump’s choice to chair the CEA, the White House’s in-house economic think tank.

The report, Miran wrote, reflected his views, not Trump’s, and is intended not as policy advocacy but to “understand the range of possible policies that might be implemented.”

Miran, 41, earned his Ph.D. in economics from Harvard University in 2010 and he has since worked in financial markets and is a fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute.

While novel, his arguments—including for tariffs—are grounded in orthodox economics. Miran is not a contrarian who assumes “all academics must be wrong,” said David Cutler, a Harvard economist who served in the Clinton administration and was one of Miran’s Ph.D. advisers. He’s “guided by the theory and evidence.”

That doesn’t mean his proposals would work. His report acknowledges a high risk that they won’t: “There is a path by which these policies can be implemented without material adverse consequences, but it is narrow.”

Economists agree that trade enables a country to both consume and produce more, and tariffs leave it worse off. Yet in the decades after Adam Smith made the definitive case for free trade in 1776, economists identified conditions under which a country might be better off imposing a tariff.

Suppose an importer is a monopsonist—a dominant enough buyer to influence the price it pays (just as a monopolist influences the price at which it sells). It could impose a $10 tariff on an imported widget, and its price, instead of rising $10, would stay the same because the exporter lowered its own price by $10 to avoid losing market share.

So consumers are unscathed. Even if they pay a bit more, that might be more than offset by tariff revenue. The rate that maximizes this net benefit is called the “optimal tariff.” Miran cites research by Arnaud Costinot of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Andrés Rodríguez-Clare of the University of California, Berkeley, that a tariff of around 20% is optimal, and up to 50% could still leave the U.S. better off.

This represents an argument for higher tariffs as a goal in and of themselves, in contrast to some Trump allies’ defense of tariffs as a negotiating tactic.

An optimal tariff policy is explicitly “beggar-thy-neighbor”: one country benefits only by hurting another. Since World War II, as the world pursued reciprocal tariff reductions, “it’s hard to find real life examples of countries motivated to pursue it in a systematic, and deliberate, way,” said Doug Irwin, a trade historian at Dartmouth College.

Optimal tariff theory has some real-world drawbacks. It doesn’t seem borne out by Trump’s tariffs on China. In an interview, Costinot noted that studies found the tariffs were mostly passed through to American importers. (Miran’s report disputed those studies.)

If other countries retaliate, as China, the European Union, Mexico and Canada did in 2018, the tariff is no longer optimal: Both sides lose. “Retaliatory tariffs by other nations can nullify the welfare benefits of tariffs for the U.S.,” Miran acknowledged.

To deter retaliation, he wrote that the Trump administration could “declare that it views joint defense obligations and the American defense umbrella as less binding or reliable for nations which implement retaliatory tariffs.” In other words, the U.S. might not defend Japan, South Korea or a fellow NATO member that retaliated.

Another problem: Tariffs only leave the U.S. better off if import prices barely rise. But in that case, consumers have no incentive to switch from imported to domestic goods, which nullifies Trump’s aim of boosting American manufacturing.

Yet another caveat is that tariffs might not reduce the trade deficit because the dollar rises in response, which makes imports cheaper and exports less competitive.

As an alternative to tariffs, Miran said the U.S. could weaken the dollar through a “Mar-a-Lago Accord,” modeled on the 1985 Plaza Accord in which the U.S. and its allies jointly acted to drive down the dollar. “After a series of punitive tariffs, trading partners such as Europe and China become more receptive to some manner of currency accord in exchange for a reduction of tariffs,” he wrote. Or, the U.S. could impose a user fee on buyers of Treasury debt.

If this triggers selling of long-term bonds, the Federal Reserve might have to buy them to limit upward pressure on long-term interest rates, Miran wrote. The Fed is more likely to cooperate with the Treasury on currency and bond interventions in return for independence on monetary policy, he wrote. (Trump has demanded more say on monetary policy. Miran has elsewhere proposed the president and state governors have more control over the Fed’s governance.)

A major question is whether a threat to withhold the defense umbrella from countries that don’t cooperate would be effective. The U.S. has no defense alliance with Mexico, Vietnam or China which account for half the U.S. trade deficit.

On Tuesday, Trump declined to rule out military force to pry Greenland from Denmark, and that he would use “economic force” to annex Canada. Both are fellow NATO members. Allies may conclude from Trump’s repeated threats against them that the U.S. defense guarantee no longer exists. Russia and China may draw the same conclusion, and seize the opportunity to increase aggression against their neighbors.

Miran himself dryly acknowledged “potentially volatile…consequences.”

Read the full article HERE.