The Federal Reserve faces a pivotal moment. With a divided committee and an economic landscape transformed by postpandemic shifts, artificial intelligence, and political forces, its traditional guideposts to the economy have become unreliable.

The neutral rate—the interest rate at which monetary policy neither stimulates nor restrains economic growth—is one such indicator that is becoming more and more elusive and irrelevant. Rather than remain fixated on it, the Fed should prioritize “doing no harm”: setting policy that avoids stalling growth or reigniting inflation.

The neutral rate, or r*, is the real (inflation-adjusted) interest rate where inflation is at target and monetary policy is neither expansionary nor contractionary. Swedish economist Knut Wicksell introduced the concept in the early 20th century to explain the business cycle. He argued that market rates below the neutral rate would expand credit and asset prices, eventually reversing as returns fell below capital costs.

In 1993, John B. Taylor formalized that concept with the “Taylor rule,” which posited that policy rates below the neutral rate would spur inflation, signaling the Fed to hike rates.

Before the global financial crisis, the Fed believed that inflation would clearly signal that the policy rate was below neutral. This is one reason for the Fed’s nonchalance toward housing market risks in the early 2000s. Price levels were muted heading into the crisis.

The Fed’s views evolved postcrisis. They returned to Wicksell’s original interpretation that the financial markets would do a better job than inflation in assessing whether policy was restrictive. This explains the central bank’s abrupt 75 basis-point cut in 2019, following a steep stock market selloff in the late 2018, as well as its aggressive actions during Covid-19.

Financial conditions historically helped gauge policy restrictiveness. But today, these correlations have broken down. Large tech stocks and AI enthusiasm drive U.S. market performance more than interest rates. Hyperscalers’ AI investment will continue—regardless of whether rates are 2% or 5%—making the S&P 500 less indicative of the economic cycle.

Inflation is also no longer a clear signal. The outlook for prices depends on a complex mix of monetary policy, money supply, tariffs, currency movements, immigration, housing supply, deregulation, government spending, and productivity. The combined effect is nearly impossible to predict. High policy rates have affected unemployment by slowing labor demand. Going forward, however, AI-driven job losses may have a greater impact than rates, and near-term employment prospects hinge on immigration policy, which is beyond the Fed’s control.

Given these uncertainties, Fed Chair Jerome Powell advocates for a data-dependent approach. He also wants more focus on inflation, which remains further from the Fed’s target than employment does. Yet, a “wait and see” approach risks a late response to slowing growth or increasing inflation.

The newest Fed governor, Stephen Miran, on the other hand, argues the administration’s policies will lower the neutral rate, justifying a more aggressive cutting cycle.

At its September meeting, Powell, Miran, and the rest of the Federal Open Market Committee members disagreed on the path for interest rates. The divergence stemmed from differing views on how restrictive current policy is. Powell described rates as “modestly restrictive,” while Miran called them “very restrictive.” In the end, Miran strayed from the group and voted for a larger cut of 50 basis points.

Underlying their disagreement is the debate over the neutral rate. But with the neutral rate so difficult to estimate these days, basing policy on it is too risky.

A third path is needed: The Fed should keep interest rates at the lowest real level that supports both stable inflation and maximum employment. This means reducing policy rates, which are dampening hiring from small businesses reliant on funding tied to short-term rates.

Cuts should be measured, however. Aggressive reductions could further ignite asset prices and stall the Fed’s already slow progress on bringing down inflation. The wealth effect from high asset prices has contributed to sticky services inflation, with nearly half of consumption driven by the top 10% income bracket. Continued upward pressure on prices could further profligacy from wealthy consumers.

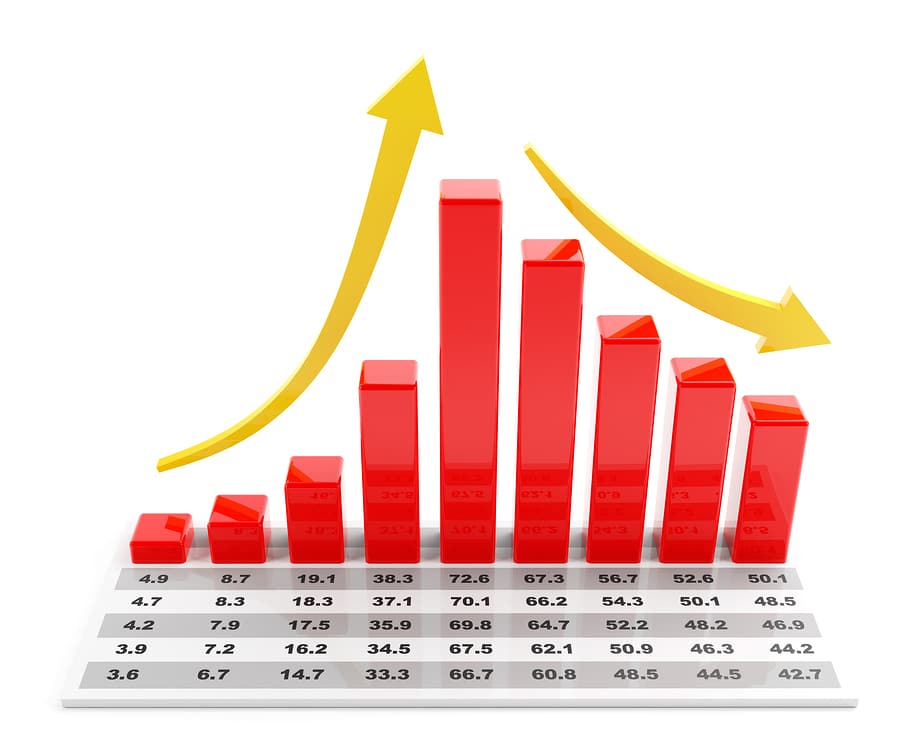

Ironically, the inflation spike from 2021 to early 2023 may explain why the Fed’s median policy rate and inflation forecasts already align with a “do no harm” approach. The rate is forecast to be 3.4% at the end of 2026, with core inflation at 2.6%. That implies just 75 basis points of cuts over the next 15 months. Investors have crowded into short-dated credit securities, betting on more aggressive easing and strong equity momentum. If the Fed cuts more gradually than markets expect, these investors may be disappointed.

Monetary policy is always uncertain. But AI and government policies are further complicating the signals the Fed uses to judge restrictiveness. Rather than trying to pinpoint the “right” neutral rate, the Fed should set its policy rate to minimize harm—supporting growth and employment, without reigniting inflation.

Read the full article HERE.