- The economy will probably head into a recession in a few years, Kenneth Rogoff says.

- The Harvard economist thinks a slowdown is coming in the second half of Trump’s term.

- The downturn will be influenced by factors like a slowing business cycle and tariffs, he suggested.

President Donald Trump’s plan to engineer America’s next economic boom will probably come up short in the coming years, according to Harvard University economist Kenneth Rogoff.

The Harvard professor and former International Monetary Fund chief economist said he believed the US economy would likely slow and enter a downturn in the second half of Trump’s term as president. That outcome will be influenced by a number of policies Trump suggested he would implement, Rogoff said, speaking to Yahoo! Finance on the sidelines of the World Economic Forum on Tuesday.

“I think the most likely scenario, with what I think are the most likely policies being passed, are strong, and then a slowdown into recession the second half of his term,” Rogoff said. “It’s just tough within the cycle not to do that.”

Rogoff highlighted some of Trump’s policies that could weigh on the economy. The president has promised to loosen regulation in the financial sector, a move that could potentially lead to “trouble down the road,” Rogoff said.

“And also, when you goose up the economy with these policies, most of which are not structural, they’re really demand policies, you’re going to get that effect,” he added of the potential for an economic slowdown.

Rogoff pointed to Trump’s tariff plan, with the president promising to levy tariffs on imports from China, Canada, and Mexico as soon as February 1.

Economists have said the tariffs could lead to higher inflation and higher interest rates, an idea Trump has pushed back on. Trump levied tariffs during his first term as president without a significant inflation increase. However, his proposals for tariff policy in his second term are more expansive, explaining the difference in inflation forecasts.

Rogoff said the inflationary impact of the tariffs could be minor, though he believed the tariffs themselves would make markets nervous and could harm growth.

“The inflationary impact is not a big deal, quantitatively,” Rogoff said. “More worrisome is that it’s chaotic, it hurts these animal spirits that he’s benefiting from. It actually leads to slower growth.”

Trump has promised to “reignite explosive economic growth” over his four years in office, adding in his inauguration speech that tariffs could lead to “massive amounts of money” pouring into the US.

Wall Street is bullish that Trump’s push to loosen regulation for businesses could boost growth. But any pro-growth policies from Trump will likely still be outweighed by “counterproductive” policies, Rogoff said, speaking in a separate interview with Bloomberg at the event.

Interest rates are also much higher than they were when Trump first took office in 2017, which is a wrinkle in any plans to juice the economy beyond already fairly robust levels of growth.

“Every campaign promise practically is something counterproductive — I mean, you can go to the tariffs, social security being not taxed, and on and on and on,” Rogoff said. “He has a lot of constraints that he didn’t face the first time. So I don’t think you can expect quite the boom we got the last time,” he later added.

Other forecasters have also issued downbeat outlooks for what could happen during Trump’s presidency. Steve Hanke, another top economist, said the US could slip into a recession as soon as Trump’s first year in office.

Read the full article HERE.

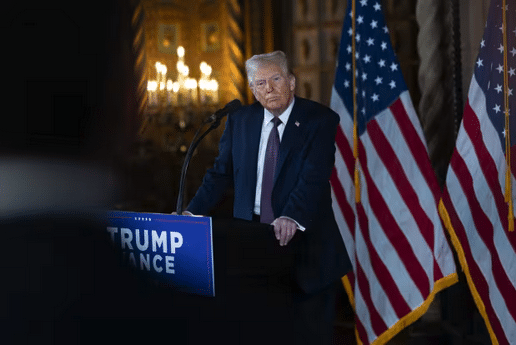

Trump says Chinese President Xi Jinping ‘knows where I stand’ when it comes to tariffs

President Donald Trump announced he is planning a 10 percent tariff on Chinese imports on Feb. 1 over the country’s role in fentanyl trafficking.

“We’re talking about a tariff of 10% on China, based on the fact that they’re sending fentanyl to Mexico and Canada,” Trump told reporters at the White House on Tuesday. “Probably February 1st is the date we’re looking at.”

When asked about a conversation he had with Chinese President Xi Jinping ahead of his inauguration this week, Trump added that “We didn’t talk too much about tariffs other than he knows where I stand.”

During his campaign, Trump threatened tariffs as high as 60 percent on goods from China. He recently pledged on Truth Social to create an “External Revenue Service” to “collect our Tariffs, Duties, and all Revenue that come from Foreign sources.”

Trump and his allies have argued that such a plan would bolster American manufacturing while making it more difficult for adversaries like China to “export their way out of their current economic malaise,” as Treasury Secretary nominee Scott Bessent told senators last week.

However, Democrats and opponents argue the cost of the tariffs would just be passed on to American consumers.

“Not only would widespread tariffs drive up costs at home and likely send our economy into recession, but they would likely lead to significant retaliation, hurting American workers, farmers, and businesses,” Rep. Suzan DelBene, D-Wash., recently said in a statement.

At a press briefing Wednesday, Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Mao Ning told reporters that “We always believe that there is no winner in a trade war or tariff war,” according to Reuters.

Trump also has said a 25 percent levy will be placed on all goods from Canada and Mexico by February.

In late November, Trump wrote on his Truth Social account that he would implement such tariffs on Jan. 20 as one of his first Executive Orders and that the tariffs “will remain in effect until such time as Drugs, in particular Fentanyl, and all Illegal Aliens stop this Invasion of our Country!”

Those promised tariffs haven’t gone into effect yet, but on Monday, Trump did sign an executive order titled “America First Trade Policy.”

“The Secretary of Commerce, in consultation with the Secretary of the Treasury and the United States Trade Representative, shall investigate the causes of our country’s large and persistent annual trade deficits in goods, as well as the economic and national security implications and risks resulting from such deficits, and recommend appropriate measures, such as a global supplemental tariff or other policies, to remedy such deficits,” the order says.

“The Secretary of the Treasury, in consultation with the Secretary of Commerce and the Secretary of Homeland Security, shall investigate the feasibility of establishing and recommend the best methods for designing, building, and implementing an External Revenue Service (ERS) to collect tariffs, duties, and other foreign trade-related revenues,” it adds.

Read the full article HERE.

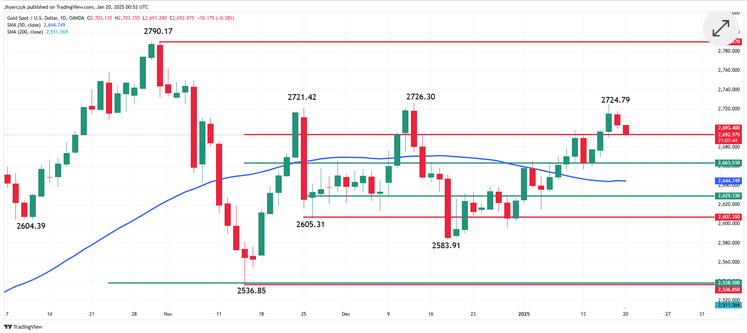

Gold prices rose in Asian trading on Tuesday as the dollar weakened sharply overnight, while traders tried to assess U.S. President Donald Trump’s policies following his inauguration.

Spot Gold rose 0.3% to $2,727.39 per ounce, while Gold Futures expiring in February gained 0.4% to $2,743.57 an ounce by 01:28 ET (06:28 GMT).

Bullion rises due to ‘safe-haven’ shine amid uncertainty

Gold traders are bracing for increased volatility as Trump begins his second term, with his anticipated policy announcements expected to influence market dynamics.

The precious metal, traditionally viewed as a safe-haven asset, has maintained its price above a one-month peak.

Market sentiment is currently shaped by the interplay between potential U.S. policy shifts and the Federal Reserve’s monetary stance.

Trump has vowed to impose new trade tariffs on its neighboring countries, and China to bring down its trade deficit. This could provide renewed strength to the dollar, thereby affecting gold prices.

The US Dollar Index fell more than 1% overnight but rebounded later in Asia hours, rising 0.3%.

A weaker dollar typically drives gold prices higher because it makes the metal cheaper for buyers using other currencies.

Traders are closely monitoring Trump’s moves to assess their impact on gold’s trajectory.

Other precious metals were mixed on Tuesday. Platinum Futures were 0.4% lower at $958.80 an ounce, while Silver Futures rose 0.6% to $31.30 an ounce.

Copper remains under pressure as tariff concerns weigh

Among industrial metals, copper prices were subdued as a combination of anticipated U.S. tariffs, prospects of a stronger dollar, and investor caution after Trump’s inauguration, weighed on the red metal.

During periods of escalating tariffs and trade tensions, such as in mid-2018 and mid-2019, copper prices declined sharply as investors anticipated reduced demand from China, the world’s largest copper consumer.

Benchmark Copper Futures on the London Metal Exchange were largely muted at $9,255.50 a ton, while February Copper Futures fell 0.6% to $4.2910 a pound.

Read the full article HERE.

Key Points:

- Analysts forecast XAU/USD could climb to $2,950 in 2025 as geopolitical risks under Trump increase safe-haven demand.

- Inflation, fiscal deficit concerns, and geopolitical risks could drive a bullish XAU/USD market during Trump’s administration.

- Tariffs may spur inflation, boosting XAU/USD.

- Weak dollar under Trump could fuel XAU/USD strength.

- Fed rate hikes could limit gold’s momentum, but inflationary pressure under Trump may support XAU/USD growth.

How Could Trump’s Tariff Policies Impact Gold Prices?

Donald Trump’s renewed focus on tariffs could have a significant influence on gold prices. By raising the cost of imports to support domestic industries, tariffs often lead to higher consumer prices. This effect could stoke inflation, which traditionally boosts gold’s appeal as a hedge.

Analysts from Goldman Sachs suggest that inflationary pressure from tariffs could push investors to allocate more funds to gold, driving its demand higher. If inflation accelerates in 2025, gold prices could gain substantial upward momentum.

Will Tax Cuts and Deregulation Weaken the Dollar?

Trump’s proposed tax cuts and deregulation are designed to stimulate economic activity. However, these measures could expand the federal deficit, potentially weakening the U.S. dollar.

When the dollar depreciates, gold tends to benefit as it becomes cheaper for investors using other currencies. Many market participants recall similar trends during Trump’s first term, when tax policies initially sparked optimism but later raised concerns about fiscal sustainability.

Experts at Morgan Stanley suggest the dollar’s performance could be a key driver of gold prices under this administration.

Could Geopolitical Risks Drive Gold Demand?

Trump’s assertive approach to foreign policy has historically heightened global uncertainty. As a result, gold’s role as a safe-haven asset may gain prominence.

Investors seeking stability during unpredictable times often turn to gold, and the potential for diplomatic tensions could increase demand. Analysts at J.P. Morgan forecast gold could average $2,950 per ounce in 2025, with geopolitical risks being a significant contributing factor.

Inflation, Fed Policy, and Powell’s Influence

Trump’s policies could create inflationary pressures, but how these intersect with the Federal Reserve’s monetary stance remains to be seen. Fed Chair Jerome Powell has indicated a commitment to taming inflation through higher interest rates if needed, which could strengthen the dollar and weigh on gold prices.

Historically, Trump has been critical of Powell, accusing him of being overly hawkish on rates. Renewed clashes between the White House and the Fed could introduce volatility to markets, further influencing gold demand.

If the Fed opts for a tighter policy stance, it may counteract gold’s bullish momentum. Conversely, if the Fed pivots or pauses rate hikes, inflationary concerns could dominate, providing additional tailwinds for gold.

Gold Prices Forecast After Trump Takes Office

With inflation risks, a potentially weaker dollar, and geopolitical concerns on the horizon, the outlook for gold appears bullish under Trump’s policy agenda.

However, traders should closely watch the interplay between inflation trends and Federal Reserve actions. Powell’s influence on interest rates and the dollar will likely remain key factors in determining gold’s direction during Trump’s administration.

Read the full article HERE.

Stephen Miran, nominated to advise Trump, has suggested high tariffs could be the price allies pay for U.S.’s defense umbrella

To serve as an economic adviser to Donald Trump, it helps to share his belief that tariffs make the U.S. richer. Not many economists meet that criterion.

Stephen Miran has made just that case. Miran, the president-elect’s choice to chair his Council of Economic Advisers, has written that the U.S. could be better off with average tariffs of around 20% and as high as 50%, compared with the current 2%.

Miran’s views are worth studying, and not just because he’s going to advise Trump. He has described tariffs as a tool, and international intervention to weaken the dollar as another, that could address a longstanding global tension: the U.S.’s economic and military support for other countries have contributed to an overvalued dollar, wide trade deficit and hollowed-out industrial base.

“Sweeping tariffs and a shift away from strong dollar policy can have some of the broadest ramifications of any policies in decades, fundamentally reshaping the global trade and financial systems,” Miran wrote in a November report for Hudson Bay Capital, where he is senior strategist.

Miran wrote the report “A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System” before he was named in late December as Trump’s choice to chair the CEA, the White House’s in-house economic think tank.

The report, Miran wrote, reflected his views, not Trump’s, and is intended not as policy advocacy but to “understand the range of possible policies that might be implemented.”

Miran, 41, earned his Ph.D. in economics from Harvard University in 2010 and he has since worked in financial markets and is a fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute.

While novel, his arguments—including for tariffs—are grounded in orthodox economics. Miran is not a contrarian who assumes “all academics must be wrong,” said David Cutler, a Harvard economist who served in the Clinton administration and was one of Miran’s Ph.D. advisers. He’s “guided by the theory and evidence.”

That doesn’t mean his proposals would work. His report acknowledges a high risk that they won’t: “There is a path by which these policies can be implemented without material adverse consequences, but it is narrow.”

Economists agree that trade enables a country to both consume and produce more, and tariffs leave it worse off. Yet in the decades after Adam Smith made the definitive case for free trade in 1776, economists identified conditions under which a country might be better off imposing a tariff.

Suppose an importer is a monopsonist—a dominant enough buyer to influence the price it pays (just as a monopolist influences the price at which it sells). It could impose a $10 tariff on an imported widget, and its price, instead of rising $10, would stay the same because the exporter lowered its own price by $10 to avoid losing market share.

So consumers are unscathed. Even if they pay a bit more, that might be more than offset by tariff revenue. The rate that maximizes this net benefit is called the “optimal tariff.” Miran cites research by Arnaud Costinot of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Andrés Rodríguez-Clare of the University of California, Berkeley, that a tariff of around 20% is optimal, and up to 50% could still leave the U.S. better off.

This represents an argument for higher tariffs as a goal in and of themselves, in contrast to some Trump allies’ defense of tariffs as a negotiating tactic.

An optimal tariff policy is explicitly “beggar-thy-neighbor”: one country benefits only by hurting another. Since World War II, as the world pursued reciprocal tariff reductions, “it’s hard to find real life examples of countries motivated to pursue it in a systematic, and deliberate, way,” said Doug Irwin, a trade historian at Dartmouth College.

Optimal tariff theory has some real-world drawbacks. It doesn’t seem borne out by Trump’s tariffs on China. In an interview, Costinot noted that studies found the tariffs were mostly passed through to American importers. (Miran’s report disputed those studies.)

If other countries retaliate, as China, the European Union, Mexico and Canada did in 2018, the tariff is no longer optimal: Both sides lose. “Retaliatory tariffs by other nations can nullify the welfare benefits of tariffs for the U.S.,” Miran acknowledged.

To deter retaliation, he wrote that the Trump administration could “declare that it views joint defense obligations and the American defense umbrella as less binding or reliable for nations which implement retaliatory tariffs.” In other words, the U.S. might not defend Japan, South Korea or a fellow NATO member that retaliated.

Another problem: Tariffs only leave the U.S. better off if import prices barely rise. But in that case, consumers have no incentive to switch from imported to domestic goods, which nullifies Trump’s aim of boosting American manufacturing.

Yet another caveat is that tariffs might not reduce the trade deficit because the dollar rises in response, which makes imports cheaper and exports less competitive.

As an alternative to tariffs, Miran said the U.S. could weaken the dollar through a “Mar-a-Lago Accord,” modeled on the 1985 Plaza Accord in which the U.S. and its allies jointly acted to drive down the dollar. “After a series of punitive tariffs, trading partners such as Europe and China become more receptive to some manner of currency accord in exchange for a reduction of tariffs,” he wrote. Or, the U.S. could impose a user fee on buyers of Treasury debt.

If this triggers selling of long-term bonds, the Federal Reserve might have to buy them to limit upward pressure on long-term interest rates, Miran wrote. The Fed is more likely to cooperate with the Treasury on currency and bond interventions in return for independence on monetary policy, he wrote. (Trump has demanded more say on monetary policy. Miran has elsewhere proposed the president and state governors have more control over the Fed’s governance.)

A major question is whether a threat to withhold the defense umbrella from countries that don’t cooperate would be effective. The U.S. has no defense alliance with Mexico, Vietnam or China which account for half the U.S. trade deficit.

On Tuesday, Trump declined to rule out military force to pry Greenland from Denmark, and that he would use “economic force” to annex Canada. Both are fellow NATO members. Allies may conclude from Trump’s repeated threats against them that the U.S. defense guarantee no longer exists. Russia and China may draw the same conclusion, and seize the opportunity to increase aggression against their neighbors.

Miran himself dryly acknowledged “potentially volatile…consequences.”

Read the full article HERE.

- Gold hits its highest level since Dec. 12

- Treasury yields pare gains after US data

- US weekly jobless claims increase more than expected

Gold prices rose to a more-than-one-month high on Thursday after the latest U.S. economic data pressured the Treasury yields further, following a soft core inflation reading this week that increased bets for a more dovish Federal Reserve policy.

Spot gold gained 0.8% to $2,718.00 per ounce as of 9:55 a.m. ET (1455 GMT), hitting its highest since Dec. 12. U.S. gold futures rose 1.1% to $2,748.60.

Initial claims for state unemployment benefits rose to a seasonally adjusted 217,000 for the week ended Jan. 11, the Labor Department said on Thursday. A Reuters poll had forecast 210,000 claims.

“The initial jobless claims were more than expected, so that signals some weakening in the labour market,” said Alex Ebkarian, chief operating officer at Allegiance Gold.

“We also saw the U.S. Treasury yields dropping, so we’re seeing the attractiveness of gold re-invigorating.”

U.S. Treasury yields pared gains and were trading near a one-week low after retail sales, jobless claims and import prices data.

Gold prices extended gains on Wednesday after data showed core U.S. inflation increased 0.2% in December after rising 0.3% for four straight months, also giving hopes for easing monetary policy.

Markets now expect the Fed to deliver 37 basis points (bps) worth of rate cuts by year-end, compared with about 31 bps before the inflation data.

Gold is seen as a hedge against inflation, but higher interest rates tarnish non-yielding bullion’s allure.

“Gold should find itself in a supportive environment, so long as market participants can hold on to expectations for Fed rate cuts in 2025,” said Exinity Group chief market analyst Han Tan.

Elsewhere, Israel airstrikes killed at least 77 people in Gaza, hours after a ceasefire deal was announced to bring an end to 15 months of war.

Spot silver rose 0.3% to $30.74 per ounce and platinum firmed 0.2% to $940.00, while palladium fell 1.9% to $943.0.

Read the full article HERE.

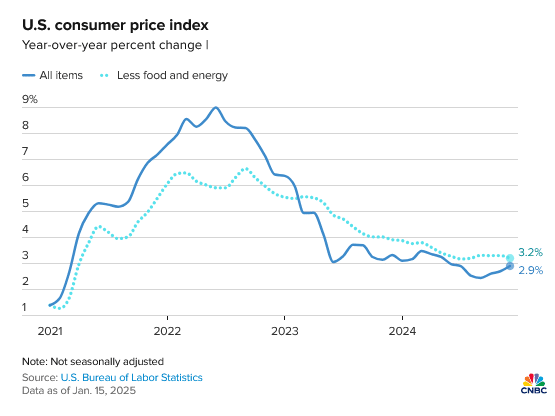

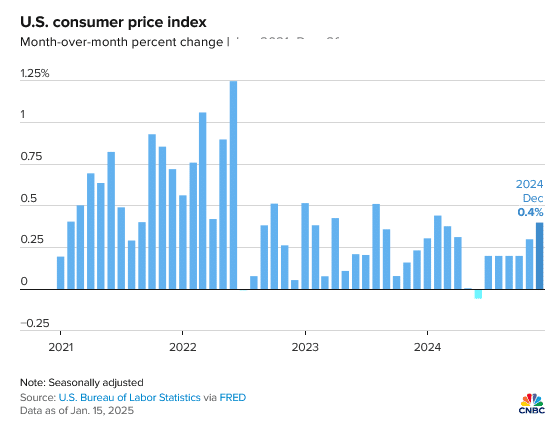

- The consumer price index increased a seasonally adjusted 0.4% on the month, putting the 12-month inflation rate at 2.9%. The annual number was in line with forecasts.

- Core CPI annual rate was 3.2%, a notch down from the month before and slightly better than the 3.3% outlook.

- Shelter prices, which comprise about one-third of the CPI weighting, rose by 0.3% but were up 4.6% from a year ago, the smallest one-year gain since January 2022.

- Stock market futures surged following the release while Treasury yields tumbled.

Prices that consumers pay for a variety of goods and services rose again in December but closed out 2024 with some mildly better news on inflation, particularly on housing.

The consumer price index increased a seasonally adjusted 0.4% on the month, putting the 12-month inflation rate at 2.9%, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported Wednesday. Economists surveyed by Dow Jones had been looking for respective readings of 0.3% and 2.9%.

However, excluding food and energy, the core CPI annual rate was 3.2%, a notch down from the month before and slightly better than the 3.3% forecast. The core measure rose 0.2% on a monthly basis, also 0.1 percentage point less than expected.

Much of the move higher in the CPI came from a 2.6% gain in energy prices for the month, pushed higher by a 4.4% surge in gasoline. That was responsible for about 40% of the index’s gain, according to the BLS. Food prices also rose, up 0.3% for the month.

On an annual basis, food climbed 2.5% in 2024 while energy nudged down by 0.5%.

Shelter prices, which comprise about one-third of the CPI weighting, rose by 0.3% but were up 4.6% from a year ago, the smallest one-year gain since January 2022.

Stock market futures surged following the release while Treasury yields tumbled.

Though the numbers compared favorably to forecasts, they still show that the Federal Reserve has work to do to reach its 2% inflation target. Headline inflation moved down from its 3.3% rate in 2023, while core was 3.9% a year ago.

“Today’s CPI may help the Fed feel a little more dovish. It won’t change expectations for a pause later this month, but it should curb some of the talk about the Fed potentially raising rates,” said Ellen Zentner, chief economic strategist at Morgan Stanley Wealth Management. “And judging by the market’s initial response, investors appeared to feel a sense of relief after a few months of stickier inflation readings.”

The inflation readings this week – the BLS released its produce price index Tuesday – are expected to keep the Fed on hold when it convenes its policy meeting later this month.

While the market cheered the CPI release, the news was less positive for workers: Inflation-adjusted hourly earnings for the month fell by 0.2%, putting the year-over-year gain at just 1%, the BLS said in a separate release.

Details in the inflation report otherwise were mixed.

Used car and truck prices jumped 1.2% while new vehicle prices also moved higher by 0.5%. Transportation services surged 0.5% and were up 7.3% year over year, while egg prices jumped 3.2%, taking the annual gain to 36.8%. Auto insurance rose 0.4% and was up 11.3% annually.

“The inflation rate is currently grappling with a ‘last mile’ problem, where progress in reducing price pressures has slowed,” said Sung Won Sohn, a professor at Loyola Marymount University and chief economist at SS Economics. “Key drivers of inflation, including gas, food, vehicles, and shelter, remain persistent challenges. However, there are signs of hope that long-term inflationary pressures may continue to ease, aided by moderating trends in critical sectors such as shelter and labor costs.”

The report comes with markets skittish over the state of inflation and the Fed’s potential response. Tariffs and mass deportations that President-elect Donald Trump has promised have increased concerns over inflation.

Job growth in December was much stronger than economists had expected, with the gain of 256,000 further raising concerns that the Fed could stay on hold for an extended period and even contemplate interest rate increases should inflation prove stickier than expected.

The December CPI report, coupled with a relatively soft reading Tuesday on wholesale prices, show that while inflation is not cooling dramatically, it also isn’t showing signs of reaccelerating.

A separate report Wednesday from the New York Fed showed manufacturing activity softening but prices paid and received rising substantially.

Futures pricing continued to imply a near-certainty that the Fed would stay on hold at its Jan. 28-29 meeting but titled more favorably towards two rate cuts through the year, assuming quarter percentage point increments, according to CME Group figures. Markets expect the next cut likely will happen in May or June.

The Fed uses the Commerce Department’s personal consumption expenditures price index as its primary forecasting measure for inflation. However, the CPI and PPI measures figure into that calculation.

The two readings likely mean that core PCE will rise just 0.2% in December, keeping the annual rate at 2.8%, according to Samuel Tombs, chief U.S. economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics.

Read the full article HERE.

The chances of a recession hitting the U.S. economy was the hot topic this time last year, but entering 2025 the issue has almost entirely disappeared. That may sound comforting but it’s also cause for alarm.

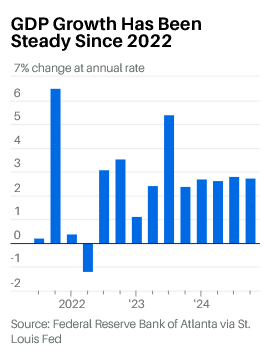

It’s easy to see why recession talk has vanished, as there are very few signs of impending collapse—GDP growth has topped 2% in eight of the last nine quarters. Seasoned investors could see an overwhelming consensus for ever-more growth as a red flag, and if the worst does happen, it means markets may swing more violently because of the unforeseen risk.

If the outlook does change, these are the warnings to watch for:

Jobs Jolt

The textbook first sign of a recession is an increase in unemployment. That leads to weaker consumer spending, which hurts company profits, which then leads to more job losses. Jawad Mian, the founder of Stray Reflections, a macro advisory for institutional investors, sees several factors that could lead to a downturn.

It may not start with high unemployment—while the jobless rate has been rising slowly, it remains historically low. Still, sticky inflation could mean real incomes are soon getting pinched again, Mian told Barron’s. There could also be a negative wealth effect if stocks and property prices stop rising so precipitously, which would hurt consumer confidence. And the labor market might weaken on its own after years of strong job growth—there’s a natural limit to how much the labor market can expand, especially if immigration is pushed down.

Trump Trauma

Which leads to the elephant in the room—President-elect Donald Trump, who has vowed to reduce immigration, slash government spending, cut taxes, and place tariffs on imports. Investors have mostly focused on his promises to reduce regulation and make it easier for U.S. firms to do business.

“The biggest risk right now is a failure to imagine the downsides,” said Mian. “We’ve reached a point of constraint in the economy.”

However, other economists have tried to put numbers on the impact of the net effect of Trump’s proposals. The National Institute of Economic and Social Research (Niesr), a London-based think tank, reckons that expelling immigrants and raising tariffs will knock 1.25% off growth from gross domestic product in the first year. In addition, it will lead to inflation in years to come—especially if Trump is able to increase the president’s influence on the Federal Reserve.

“These negative effects, which hurt consumption, investment and exports, more than offset benefits from supply-side policies, such as easing regulation, even in the medium term,” said Niesr economist Paul Mortimer-Lee. If Trump also radically reduces government spending, the usual cushions against a downturn would be undermined, and “the economy would likely enter recession,” he added.

Market Misery

For investors, one key thing to remember is that the economy and the stock market aren’t the same thing. While they do feed off each other, the stock market can perform well even without strong economic growth. It’s also the case that the economy can keep growing without stocks continuing to do well. Goldman Sachs which sees slim odds of recession, predicts a “lost decade” for stocks with returns after inflation of 3% or less on average.

At the beginning of 2024 there were more than a handful of forecasts for an economic contraction. The year before that, at the end of 2022, respected commentators including Bloomberg Economics and Deutsche BankDBK+2.51% predicted it was almost certain that the U.S., in the near future, would enter recession. Even the Federal Reserve, which was raising interest rates at the fastest pace in a generation, had a recession in its staff forecasts as late as July 2023.

Cursed Curve

The yield curve has always been an important indicator. One of the market’s favorite harbingers of recession—whether it is two quarters of contraction, or a year-over-year drop in output, or just a sustained economic downturn—is when the two-year government note yield is higher than the 10-year yield. It was inverted from mid-2022 through September of last year. But since then, the longer-term rates have pushed substantially higher.

In a FactSet survey of 85 institutions, none of them predicts an economic contraction in 2025. Goldman Sachs reduced the odds of a recession—it now sees the chances at about 15%. The Fed upgraded its forecast for gross domestic product to rise 2.1% next year.

The bottom line is that—perhaps more so than in the past two years when the market has gone from strength to strength—it’s always important to keep your wits about you.

“We are in this strange backdrop where investors believe that there is no recession risk, no risk of earnings disappointments,” said David Rosenberg, founder of Rosenberg Research. “We are in a once-in-a-lifetime situation where the concept of risk has been totally distorted—an investment world where there is no more differentiation between what has traditionally been risky and what is riskless.”

A recession may not be in the cards for 2025. But there is likely more risk out there than most people are mitigating for.

Read the full article HERE.

Baby Boomers may have hit the jackpot money-wise, but many attribute their wealth to financial planning and professional advice rather than good timing.

Millions of Baby Boomers are rapidly reaching retirement age in a “silver tsunami” that is placing a renewed focus on how this generation feels about their finances. According to Charles Schwab’s Modern Wealth Survey, 66% of Boomers believe they are in a better position to reach their financial goals than previous generations.

How did this generation find themselves to be so well positioned financially?

A majority of Boomers feel they have a positive relationship with money, which gives this generation a strong financial foundation. In addition, more than 3 in 5 Boomers (63%) are actively investing today, and they overwhelmingly expressed confidence in their investment strategy and ability to reach their financial goals. Boomers attribute this confidence to having more ways to build wealth (68%), more investment options (64%), and more accessibility to investing in general (58%). Financial confidence doesn’t always come easily, but we hear common themes from those who share it.

1. Do your research and seek professional advice

In today’s world, there is an overwhelming amount of information online, and it can be difficult to discern what financial advice is trustworthy. While “finfluencers” may be gaining traction among younger generations, Boomers are most likely to use a financial professional/institution (such as a financial adviser, investment firm, or accountant) for financial advice. They noted the top reasons for trusting these professional sources are their proven track record of success (53%) and the proper financial certifications and credentials (45%).

A financial adviser can help you navigate the complex world of investing, but it’s important to carefully determine which professional resource is right for you and best meets your needs. Are you seeking help with budgeting and savings goals or more complex guidance around financial planning, wealth management and tax planning? If you are seeking assistance with financial decisions, you will want to understand the different designations you encounter and create a list of questions to ask a potential adviser to find the right fit.

2. Have a financial plan

When it comes to managing your finances and preparing for retirement, the quote “if you fail to plan, you plan to fail” could not be more true. A financial plan is essentially a roadmap to attain your goals. It is easier and more affordable to get a financial plan today than it’s ever been before, whether you get started with a do-it-yourself digital financial plan or have an in-depth conversation with a professional.

Boomers noted that once they created a financial plan, they felt more in control of their finances and in turn more confident they would reach their financial goals.

While more than one-third of Boomers have taken the necessary steps to document their financial plan (38%), another third (34%) have only thought about their financial goals. It’s important that you discuss your financial goals and ensure you have a plan in place for your situation. Many firms, including Schwab, offer free online tools and education and employ Certified Financial Planners® that you can meet with on a one-time or ongoing basis.

3. Have an investment strategy

An investment strategy goes hand-in-hand with a financial plan. In fact, Schwab’s first investing principle is to establish a financial plan based on your goals, as these will help guide how conservative or aggressive your strategy should be. Are you saving for a dream trip, a second home, or a child’s education? Knowing your goals will help you determine if you need a strategy focused on growth or stability.

The next step is to build a diversified portfolio based on both your capacity to take on and tolerate risk. While most firms offer you the option to invest on your own, consulting a financial adviser can help simplify the process of identifying the products and services that best meet your needs.

4. Stay engaged

Having a clear vision of your financial goals is important, but equally crucial is ensuring you stay on track. Asset classes perform differently, and it’s nearly impossible to predict which ones will perform best in a given year. That’s why regularly reviewing how your investments are performing and how your assets are allocated is important. The market’s fluctuations can shift your portfolio’s balance, so periodic adjustments may be necessary. Saving for retirement is one of the most crucial goals for many investors, so it’s important to make time for ongoing reviews to ensure your strategy aligns with your evolving goals and financial circumstances.

Remember, growth is not always linear, and even during times of market uncertainty it is important to keep your eyes on the prize. This is a great time to be an investor, especially as more people recognize that investing at any stage of life is about taking ownership of your financial life and achieving your financial dreams and goals.

Read the full article HERE.

Gold prices rebounded on Friday as uncertainty surrounding the incoming Trump administration’s policies lifted safe-haven appeal, even as a stronger-than-expected U.S. employment data reinforced expectations the Federal Reserve might not cut interest rates as aggressively this year.

Spot gold was up 0.6% to $2,685.38 per ounce as of 9:40 a.m. EST (1440 GMT), while U.S. gold futures rose 1.3% to $2,726.10.

Gold prices briefly slipped to $2,663.09 an ounce after data showed the U.S. added 256,000 jobs last month, compared with economists’ estimate of a rise of 160,000. The unemployment rate stood at 4.1%, compared with a forecast of 4.2%.

Bullion prices, however, quickly rebounded and are now trading near their highest levels since Dec. 13, poised for a weekly gain of more than 1%.

“Gold’s price action points to a lack of committed sellers of the metal; a diffidence well-learned from last year’s remarkable rise,” said Tai Wong, an independent metals trader.

“The momentum from the knee-jerk reaction faded quickly and the short-term traders and programs that sold reversed quickly.”

The dollar rallied while U.S. stock futures fell sharply after the jobs data. Markets show traders now expect the Fed to cut interest rates by just 30 basis points over the course of this year, compared with cuts worth about 45 basis points before the data.

“Gold is still acting resilient in the face of a much stronger-than-expected jobs report … One of the factors that’s been supporting gold is this uncertainty that we’ve seen going into the (U.S. presidential) inauguration,” said David Meger, director of metals trading at High Ridge Futures.

As President-elect Donald Trump’s Jan. 20 inauguration approaches, investors are anxious about his vow to impose tariffs on a wide range of imports, fearing they could fuel inflation and further limit the Fed’s ability to lower rates.

While bullion is prized as a safeguard against inflation, high interest rates dull its allure as a non-yielding asset.

Spot silver gained 1% to $30.43 per ounce, platinum firmed 0.7% to $964.90 and palladium added 2.5% to $949.25. All three metals were headed for weekly gains.

Read the full article HERE.