Governments are buying up gold as they see it as a safe investment – and, in some cases, a tool for evading Western sanctions

Gold prices have surged this year as investors seek safe investments amid a spike in economic uncertainty unleashed by US President Donald Trump’s tariff policies.

But economists say that there is another important factor driving the rally: purchases by central banks.

In this explainer, we explore why central banks are increasingly turning to gold assets, how that is driving a long-term structural shift in demand for the metal, and what that means for gold prices going forward.

Why are central banks buying up more gold?

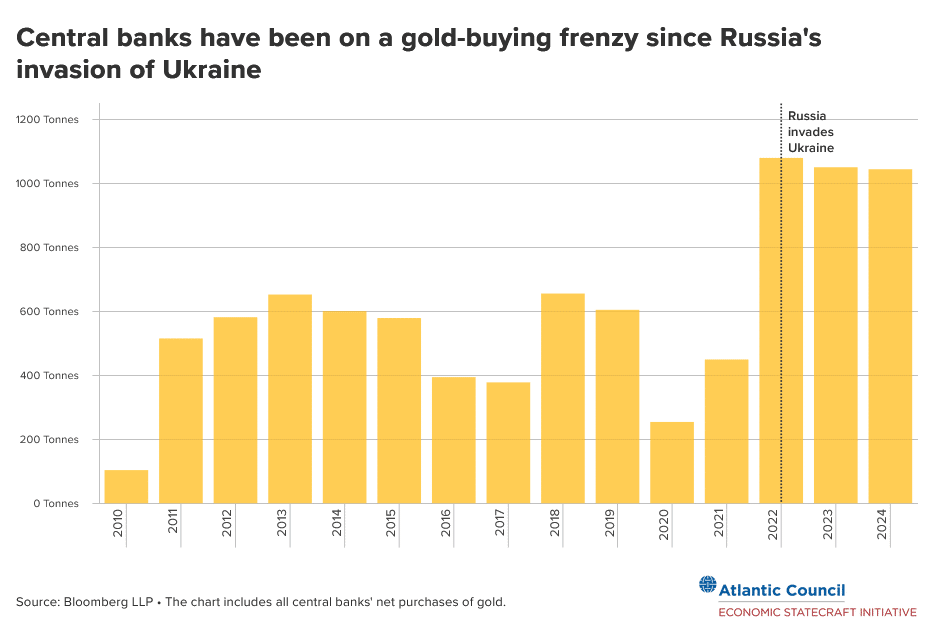

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and the wave of Russian asset freezes by Western countries that followed “marked a turning point” for the way central banks viewed gold, according to a report by Goldman Sachs Research.

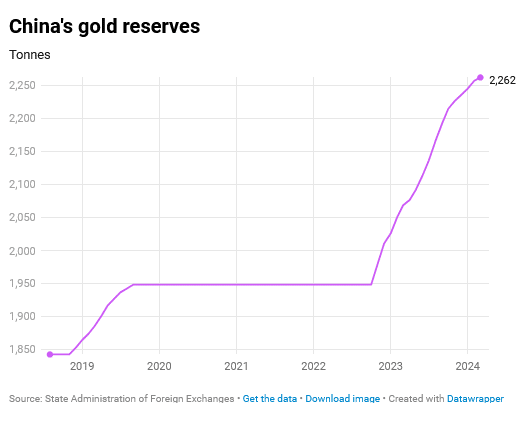

Central banks’ purchases of gold have increased fivefold since the invasion began, and demand from governments is expected to remain high for some time to come, giving gold prices an “ongoing boost”, the report said.

Countries are increasingly experimenting with creating gold-backed digital assets and trading systems that bypass the dollar-denominated financial system, according to an article by Kimberly Donovan and Maia Nikoladze of the Atlantic Council’s Economic Statecraft Initiative published earlier this month.

“In many cases, these initiatives are for purely economic benefits,” the article said. “However, gold is also being used by US adversaries to evade sanctions or finance activities that counter US national security interests.”

What are central banks’ gold asset positions now?

The global average is roughly 20 per cent, but there is a divergence between developed markets and emerging markets, according to Goldman Sachs.

Developed markets tend to have larger gold holdings – partly as a legacy of the gold standard era when sovereign money supplies were linked to the commodity – that leave them with a higher proportion of their reserve assets in gold.

For example, central banks in the United States, Germany, Italy and France hold more than 70 per cent of their reserves in gold, as of the first quarter of 2025.

China, on the other hand, holds about 5 per cent of its reserves in gold, as foreign currencies comprise a higher proportion of emerging markets’ central bank holdings, according to Goldman Sachs.

Japan’s holdings of gold are at about 6 per cent.

Goldman Sachs views the global average of about 20 per cent as a plausible medium-term target for large emerging central banks.

What is the outlook for gold?

Joni Teves, a precious metals strategist at UBS, said on May 15 that gold prices could reach US$3,500 per troy ounce this year in an “upside scenario”. The bank expects the gold rally to extend into next year and for prices to stabilise at higher levels further out.

“The case for adding gold allocations has become more compelling than ever in this environment of escalating tariff uncertainty, weaker growth, higher inflation and lingering geopolitical risks,” Teves said.

“The current backdrop wherein global trade, economic and geopolitical relationships may be changing reinforces the need to diversify into safer havens like gold,” she added.

Goldman Sachs predicts that gold will rise to US$3,700 a troy ounce by the end of 2025 due to “renewed appetite” from investors and a long-term structural shift in demand from central banks.

Meanwhile, exchange-traded funds (ETF) are also beginning to join the gold rally.

State Street Global Advisors said in a report issued in May that global gold ETF physical holdings are still down 18 to 20 per cent from the 2020 pandemic peak, which indicated that there is “plenty of scope” for investors to “re-engage” in buying gold as they assess the macro market conditions in the second half.

Read the full article HERE.

Goldman Sachs sees gold as a far better hedge against a collapsing dollar than bitcoin.

Over the past few decades, when U.S. interest rates rose, investors would tend to sell gold and buy U.S. Treasuries, seeking higher yields.

But that long term relationship broke down in February 2022, when western financial authorities moved to freeze Russia’s central bank assets upon President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

This was a wake up call, says Lina Thomas, commodity strategist at Goldman Sachs. Investors hold Treasuries or Euros because they are risk free, but if those assets can be frozen or confiscated by foreign politicians “then we have a problem.”

According to Goldman’s analysis, Russia was careful to repatriate its gold reserves held abroad.

But freezing assets is not just a problem for Russia. It damages the global system when you put in sanctions, says Thomas (speaking on a webinar hosted by energy investing consultancy Veriten).

With little faith among investors that the U.S. will be able to rein in trillion-dollar deficits, Treasury bonds are not the safe haven they used to be, so other international central bankers have decided to add to their gold piles as well.

Before 2022, central bank purchases were 17 tons per month, says Thomas. Since the Ukraine war they have grown to an average of 22 tons per month, but a remarkable 94 tons per month year-to-date.

China (the biggest gold mining country, which restricts exports) aims to grow gold holdings to 20% of reserves. Russia, the no. 2 miner and biggest exporter, has been happy to sell into the ongoing gold frenzy, though much of their supply is now routed through the likes of formerly non-gold-exporting Armenia and Kazakhstan.

The central bank gold buying binge should continue for at least another two years. That’s enough demand, figures Goldman, to drive the price up to $4,000 an ounce, a roughly 30% rise from a current $3,400.

Many central banks store their gold in Switzerland, which has vast vaulting capabilities. As the gold prices keeps rising, it becomes cheaper to store. “You can get to 20% of reserves either by increasing the volume or when the notional value goes up.”

Would this trend reverse if peace broke out? Not much, says Thomas, who did her Phd thesis at Harvard on the history of the dollar as safe haven asset. “Once you cross the Rubicon it’s a little bit tricky to come back from that,” she says. Gold allocations are likely to be sticky. It might take 20 years for macro allocators to regain enough trust to sell gold again, says Thomas.

And sell for what anyway? Bitcoin? Silver? Oil?

Daan Struyven, Goldman’s co-head of global commodities research, says the risk-reward analysis favors gold. Both bitcoin and gold are up a lot in the past three years, and the limited supply of each asset “gives confidence to investors who are worried about runaway inflation that may be caused by aggressively increasing the money supply.”

“Bitcoin is more volatile and sensitive to drawdowns, and more positively correlated with tech equities. Bitcoin and equities both do well when risk sentiment is positive,” says Struyven.

So if you want to protect against equity downside risk, “the lower correlation and lower volatility imply a pretty significant positive allocation to gold,” he says.

It’s unlikely gold miners will suddenly find big new mines; good reserves have already been depleted, going deeper takes time. Every year miners add roughly 1% to the total gold in circulation.

As for oil, Goldman sees West Texas Intermediate falling to the low $50s/bbl by mid 2026 as supply growth outpaces sluggish demand.

Why not buy silver? Thomas gives three reasons: Silver tarnishes over time, it degrades. Gold keeps its form, is far scarcer and because gold is 100 times more valuable pound-for-pound, you can move your billion dollars of buillion in a suitcase instead of the convoy of trailers you’d need for the same value of silver. Also, central banks have no interest in owning silver. It’s not recognized as a reserve asset by the IMF and is not present in any modern central bank balance sheet. Silver is more of an industrial metal, and because demand is pro-cyclical (for solar panels, electronics, etc) it is not a good hedge against economic downturn.

The gold market is just .5% of the value of the equity market, says Thomas. So even a tiny shift in allocation will have an outsized impact. For central banks the higher the price of gold goes, the easier it becomes to store — they’ll need fewer ounces to build a 20% dollar denominated allocation.

Still not sold on the barbarous relic? Just buy blue chip equities. Priced in grams of gold, the S&P 500 is down 30% since 2022 to 58 grams.

Read the full article HERE.

On April 22, gold prices reached $3,500 a troy ounce, a record that is roughly double what it was three years ago. Gold has been appreciating in value at a record pace as many other financial assets struggle. This was the case during the 2008 global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, as well. What is different this time, however, is that the price increase has been driven not just by investors but also by central banks. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the Group of Seven’s (G7’s) subsequent imposition of unprecedented sanctions on Russia, central banks that are worried about getting sanctioned, want to protect themselves from a potential global financial crisis, or both have been stacking up gold at record levels.

Governments and private actors alike are giving gold’s role in the global financial system a boost, but with a twenty-first-century twist. Individual countries and groups of countries are experimenting with creating gold-backed digital assets and trading systems that bypass the dollar-denominated financial system. In many cases, these initiatives are for purely economic benefits. However, gold is also being used by US adversaries to evade sanctions or finance activities that counter US national security interests.

The rise of gold-backed currencies that circumvent the US banking system, coupled with sanctioned regimes’ growing interest in the adoption of alternative currencies and payment systems, could create a massive blind spot for US financial intelligence and sanctions enforcement efforts. To reduce the proliferation of these alternatives to the dollar-based financial system, the United States should temper its use of coercive economic measures that can cause gold prices to rise and promote dollarization through trade and investment ties, especially with third countries impacted by sanctions on US adversaries.

Why Russia is interested in gold

Russia’s central bank is among the top holders of gold in the world, having built gold reserves from 2014 to 2020 to hedge against Western sanctions. While the central bank’s gold reserves have not increased substantially since 2020, Russia’s Ministry of Finance is thought to be buying gold from domestic producers without reporting it. In 2021, the Ministry of Finance doubled the share of gold in Russia’s National Wealth Fund to 40 percent.

After the West froze $300 billion of the Russian central bank’s assets in response to Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, this gold-hoarding strategy paid off. As gold prices skyrocketed this year, the value of Russia’s gold reserves increased by $96 billion, offsetting one-third of the frozen assets.

Gold has also played a major role in Russia’s illicit trade. For example, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), a BRICS+ member and a global hub for gold trade, as well as Turkey, have engaged in cash-for-gold trade with Russian banks. The Russia-based Lanta Bank and Vitabank received twenty-one shipments of currencies such as US dollars, euros, UAE dirhams, and Chinese renminbi worth $82 million from the UAE and Turkey in exchange for Russian gold. Late last year, the United States and United Kingdom sanctioned the network of entities and individuals involved in Russia’s illicit gold trade due to their role in generating revenue for Russia’s war chest. Additionally, Britain’s National Crime Agency published a red alert in late 2023 on gold-based illicit trade and sanctions circumvention.

Apart from using gold for reserves and sanctions evasion, Russia is also trying to leverage the BRICS+ grouping as a platform to advocate for the creation of a gold-backed BRICS+ currency. It remains to be seen if the group makes any tangible progress ahead of the next BRICS+ Summit in Brazil in early July. In the meantime, tracking the rise of gold-backed currencies and alternative payment systems across the world offers valuable insights into how they could be used for sanctions evasion.

The rise of gold-backed stablecoins

Gold-backed stablecoins—cryptocurrencies whose prices are pegged to gold—offer the most valuable property of gold, which is stability during financial uncertainty. They are also logistically more convenient to store and sell than physical gold. Companies such as Paxos and Tether capitalized on these qualities, creating gold-backed stablecoins in 2019 and 2020, respectively.

Usually, each token of gold-backed stablecoin corresponds to a specific amount of gold. For example, by purchasing one unit of Tether Gold (XAUT), investors receive the ownership rights of one troy ounce of physical gold on a specific gold bar with a serial number. Each gold bar weighs four hundred ounces on average, so if investors would like to redeem a gold bar, they have to own units worth one full gold bar. Issuers of these stablecoins hold gold reserves in safe vaults, typically in the United Kingdom or Switzerland. Third parties regularly audit gold reserves to confirm that the supply of tokens does not exceed the amount of gold held by issuers.

Governments are now following the lead of crypto companies. Earlier this month, for example, the Kyrgyz Ministry of Finance announced that it will launch a gold-backed stablecoin called USDKG in the third quarter of 2025. The Kyrgyz Ministry of Finance holds gold reserves worth $500 million and plans to expand that number up to $2 billion. (This is separate from the gold reserves held by the National Bank of the Kyrgyz Republic, which was among the top buyers of gold in the last quarter of 2024.) USDKG will not track the price of gold, unlike well-established stablecoins such as Paxos Gold or Tether Gold. Instead, it will be pegged to the dollar but solely backed by gold reserves. USDKG holders will be able to redeem gold, other crypto assets, or fiat currency.

The reported objective of the gold-backed stablecoin is to facilitate cross-border inflows of remittances, which make up one-third of Kyrgyzstan’s gross domestic product. Russia accounts for more than 90 percent of remittances that flow into Kyrgyzstan, sent by migrant workers back to their families. Kyrgyzstan has not yet launched the stablecoin, but if it’s going to be used to facilitate cross-border flows with Russia, then there is a chance that certain actors could use USDKG to export sanctioned goods to Russia outside of US authorities’ oversight. Financial institutions in Kyrgyzstan have already been sanctioned for their involvement in Russia sanctions evasion schemes by the United States.

For example, earlier this year, the Treasury Department sanctioned Kyrgyzstan-based Keremet Bank for facilitating transactions on behalf of US-sanctioned Russian bank Promsvyazbank. The Kyrgyz Ministry of Finance sold the controlling shares of Keremet Bank to a firm connected to a Kremlin-linked Russian oligarch in 2024. According to the Treasury press release, the transaction was intended to turn Keremet Bank into a sanctions evasion hub that would enable Russia to receive payments for exports and pay for imports. Given sanctioned Russians’ strong interest in taking advantage of Kyrgyzstan’s financial system to import restricted technologies, they will likely be drawn to USDKG because of its ability to process transactions with Kyrgyz entities while completely bypassing the US banking system.

How the US can stem the digital gold rush

It is no coincidence that stablecoins account for 63 percent of all illicit crypto transactions and have become a preferred tool for sanctions evasion. They attract sanctioned entities because of their ability to transfer value pseudonymously with high speed and at low cost. While the US Senate recently advanced the GENIUS Act to regulate stablecoins, one of the major deficiencies of the bill is that it does not adequately regulate offshore stablecoin issuers. Even if put into law, the GENIUS Act would fail, for example, to regulate Tether, the largest offshore issuer of dollar-pegged stablecoins, which has been the subject of federal investigations because of its alleged widespread use by terrorist groups and Russian arms dealers.

Unlike US-issued or dollar-backed stablecoins, foreign-issued gold-backed stablecoins such as USDKG will likely escape US regulation because they don’t have a touchpoint with the US banking system. Their proliferation, along with gold-backed trading schemes, is driven to a large extent by the United States’ weaponization of the dollar, as well as uncertainty over US trade policy.

The United States has the power to indirectly reduce gold prices and encourage the adoption of dollar-backed assets by returning to being the provider of stability in the global economy. That can be achieved by dialing down the use of tariffs and other economic measures that could cause governments and private actors to turn to gold.

At the same time, the US government should promote the dollarization of economies such as Kyrgyzstan’s by continuing to provide financial assistance and deepening trade and investment ties with other third countries impacted by sanctions against Russia. Doing so will help close gaps in US financial intelligence, strengthen US sanctions enforcement, and lower the demand for currencies outside the dollar-based financial system.

Read the full article HERE.

Jamie Dimon said he can’t rule out the possibility of stagflation as the US grapples with huge risks from geopolitics, deficits and price pressures.

“I don’t agree that we’re in a sweet spot,” the JPMorgan Chase & Co. chief executive officer said in a Bloomberg Television interview at the lender’s Global China Summit in Shanghai. The US Federal Reserve is doing the right thing to wait and see before making changes to interest-rate policy, he said.

Fed officials have held interest rates steady this year amid a solid economic backdrop and uncertainty about government policy changes — like tariffs — and their potential impact on the economy. Policymakers have said they see an increased risk of confronting both higher inflation and unemployment.

Earlier this month, the US and China agreed to sharply reduce tariffs for 90 days to hammer out a new agreement, in what promises to be difficult rounds of talks between Washington and Beijing. US President Donald Trump’s tariffs on China will likely remain at a level expected to severely curtail Chinese exports after the 90-day truce, analysts and investors say.

“I don’t think the American government wants to leave China,” Dimon said. “I hope they have a second round, third round or fourth round and hopefully it will end up in a good place.”

Trump’s chaotic tariff announcements and efforts to shrink or shutter government agencies have stoked concerns about trade, inflation, unemployment and a potential recession. Companies are pausing expansion, including lucrative mergers and acquisitions handled by Wall Street dealmakers, bank executives have said.

Dimon’s comments expand on remarks he made in recent interviews, when he warned against complacency and said recession remains a possibility, adding that many of the effects of the tariffs are yet to be seen. Volatility caused by the turmoil has continued to boost JPMorgan’s stock-trading business, which notched record revenue in the first quarter.

JPMorgan, the biggest US bank, also launched its “Center for Geopolitics” this week with research on Russia and Ukraine, the Middle East and global rearmament.

The unit “is both for us, and it’s also to educate clients,” Dimon said. “Clients ask us all the time, What should we do about this country? How do you look at risk?”

JPMorgan among others have indicated that the uncertainty from Trump’s policies may cause clients to sit on the sidelines. Troy Rohrbaugh, co-CEO at JPMorgan’s commercial and investment bank, said earlier this week that its investment-banking fees could fall by a percentage in the mid-teens compared to a year ago — more than analysts had predicted.

Dimon said the US has to “attack the deficit problems,” and he also understands why investors may be cutting US dollar assets.

On Wednesday night, House Republican leaders released a new version of Trump’s massive tax and spending bill with a higher limit on the deduction for state and local taxes and other changes in a bid to win over warring GOP factions to support the legislation.

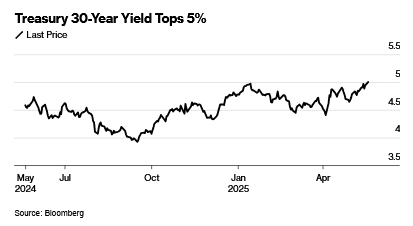

US Treasuries on Wednesday extended their recent selloff, with longer-term securities getting hit the hardest and an auction of 20-year debt receiving a relatively tepid reception. The selloff at one point pushed the yield on the 30-year bond up by as much as 13 basis points to almost 5.10%, its highest level since 2023.

“I don’t worry about short-term fluctuations in the dollar,” Dimon said. “But I do understand people might be reducing dollar assets.”

Read the full article HERE.

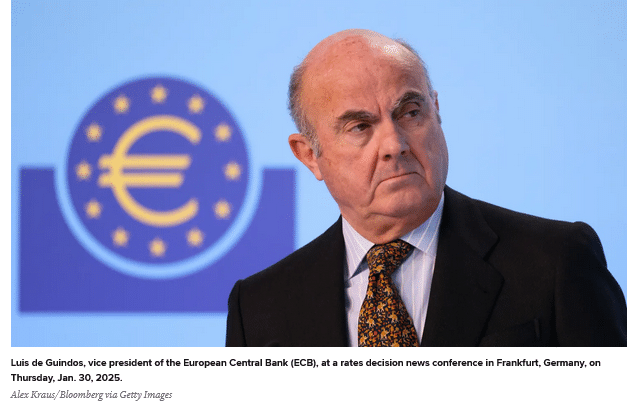

- A “fundamental regime change” could be underway in financial markets, according to the European Central Bank.

- The ECB suggested that investors seem to be rethinking U.S. assets.

- ECB Vice President Luis de Guindos told CNBC that uncertainty was now the “name of the game.”

The European Central Bank on Wednesday said a “fundamental regime change” could be underway in financial markets as investors appear to be reassessing how risky U.S. assets really are in the wake of trade tariffs.

In its latest Financial Stability Review, the central bank discussed the recent spike in market volatility off the back of global trade tensions driven by U.S. tariff policy.

Markets have been reacting sensitively to the frequent updates around trade and levies from the U.S. and its trading partners. Stocks first tumbled when U.S. President Donald Trump announced sweeping tariffs, before rebounding when he declared a temporary 90-day pause on duties.

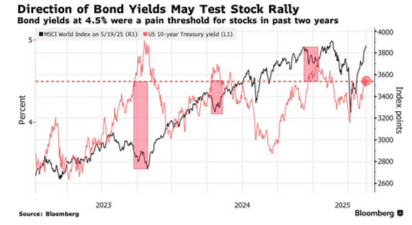

“During the turmoil, market functioning – which can be thought of as the ability to trade financial assets quickly without moving prices inordinately – in euro area financial markets held up well,” the ECB noted. “This was despite some atypical shifts away from some traditional safe havens like US Treasuries and the US dollar.”

While this could have been linked to technical factors, the ECB said, it might have also had broader triggers.

“These moves might also have reflected perceptions of a more fundamental regime change, with investors seeming to reassess the riskiness of US assets, possibly leading to broader shifts in global capital flows,” the ECB noted. “This would have potentially far-reaching consequences for the global financial system.”

ECB Vice President Luis de Guindos on Wednesday suggested to CNBC that there was a risk of a market correction down the line. Two key things to currently consider are elevated valuations and strong uncertainty, he told CNBC’s Annette Weisbach.

“Markets are very benign with respect to this scenario. They believe that, you know, growth is going to be low, but we are not going to enter into a recession, inflation is going to decline, and monetary policy will follow suit,” de Guindos explained.

Risks could still emerge, and various issues such as what could happen regarding trade and fiscal policies and regulation from the U.S. government are unclear, he said.

“And these elements give rise to volatility. I think that volatility is, perhaps, you know, the consequence of these two elements …, valuations and uncertainty.”

In its report, the central bank pointed out that it had previously warned about “vulnerabilities posed by high valuations that are not backed by fundamentals,” saying that “this source of risk has now partly materialised.”

Trump’s reciprocal tariff announcement was the trigger for this, the ECB said.

Uncertainty the ‘name of the game’

Taking a broader view, de Guindos said uncertainty linked to U.S. trade, fiscal and regulatory policy was now the “name of the game” throughout financial markets and the global economy. The question was now what this uncertainty and any eventual policy moves meant for Europe and financial stability in the euro area, he suggested.

Looking at inflation and economic growth, de Guindos reiterated that tariffs would be “detrimental” to growth, while the impact on prices was less clear.

In the short term, tariffs would raise the prices of imported goods, while at the same time depressing demand, which could offset the higher costs, he said.

Long-term implications could look very different.

″[In the] long term, if tariffs and trade distortions give rise to fragmentation that will be detrimental to the supply chain, and that could increase the cost of the corporates. And that could be inflationary,” de Guindos said.

Earlier this week, the European Union put out its latest economic projections, cutting its 2025 gross domestic product forecast for both the EU and euro area to 1.1% and 0.9% respectively. This compares to a previous estimate of 1.5% growth for the EU and a 1.3% expansion for the euro area.

Headline inflation is meanwhile expected to slow, falling below the ECB’s 2% target in 2026.

Read the full article HERE.

U.S. debt is a spending problem, which neither party wants to stop.

Moody’s Ratings service waddled in Friday to state the obvious, which is that the U.S. is on an unsustainable debt trajectory. We’d like to know where Moody’s was when the Biden Administration was spending at record levels, but there’s still a warning here for the Republicans now in charge in Washington.

Moody’s downgraded U.S. debt to a notch below its top rating, citing chronic budget deficits and rising debt-service costs. The rating agency lagged behind S&P Global Ratings and Fitch, which downgraded the U.S. in 2011 and 2023, respectively. Moody’s may have been late because it believes in the Keynesian model that government spending lifts economic growth.

Markets on Monday reacted poorly to the downgrade, as well as comments by Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent that there may be more bad tariff news coming. He said the April 2 “reciprocal” tariffs could return for some countries if they don’t agree to President Trump’s supposedly generous terms. The 30-year Treasury bond yield hit 5% for the first time since autumn 2023, before falling back, and the 10-year appears to be settling near 4.5%.

Moody’s is no oracle, but its downgrade is a moment to explain America’s real deficit and debt issue. The problem is spending, which neither political party wants to restrain. More revenue from faster economic growth would help, but supply-side growth policies have ebbing political support, even in the GOP.

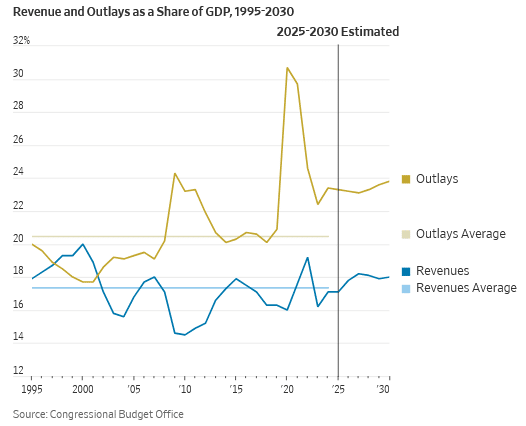

The nearby chart tells the Washington fiscal story as a share of gross domestic product from 1995 through the present and estimated through 2030. Revenues have held within a fairly narrow band not far off from the 17.2% average from 1995 through last year.

Revenues fell with the 2008-2009 recession, and again modestly and for a short time with the Trump tax reform that began in 2018. But they are back to the long-term trend and on current policy will increase over the next decade and beyond.

Spending is a different tale. The average for outlays from 1995-2024 is 21.1%, but they spiked to more than 24% amid the Obama spending blowout after the financial panic. The GOP Congress elected in 2010 shrunk outlays back down to the average, mainly by cutting domestic and defense discretionary spending. Entitlements kept growing.

Then the pandemic hit, and outlays exploded under Presidents Trump and Biden. They’ve declined some in the last two years, but they were still 23.4% of GDP in fiscal 2024.

That left a budget deficit of 6.4% of GDP last year, which is unheard of when the economy is growing and there is no war or emergency. The Congressional Budget Office says spending will keep growing as a share of the economy, as entitlements continue to boom. Spending is the debt driver.

Republicans could do something about this but may not have the votes. DOGE has cut around the edges, but President Trump won’t touch Medicare or Social Security. Too many Republicans won’t even fix Medicaid, which has soared since ObamaCare expanded coverage to able-bodied young men. The current House budget bill doesn’t do much more than sustain the Biden spending path.

Democrats and the press want to blame the tax portion of the House GOP bill, but that mainly keeps the current tax rates. The new Trump tax ideas—expanding social handouts via the tax code and state-and-local tax deductions for wealthy blue-state residents—do nothing for growth.

But its pro-growth tax provisions will at least kick back some revenue to Treasury, unlike more social-welfare spending. And if the bill fails to pass, the economy will be hit with a $4.5 trillion tax increase. Add Mr. Trump’s tariff tax of some $300 billion or so, and the economy might go into recession. Then watch spending and the deficit explode. Extending the lower tax rates and deregulation are crucial to keep the economy growing.

None of this is a fiscal or financial crisis, at least not yet. The dollar’s reserve-currency status gives the U.S. a unique borrowing privilege. There will always be buyers for Treasury bonds, though the question is at what price? Higher interest rates mean net interest on the federal debt is now 3% of GDP and closing in on $900 billion a year.

The Moody’s downgrade joins the list of warnings to Washington that the country needs better economic and fiscal policies. We wish we could see more signs of them.

Read the full article HERE.

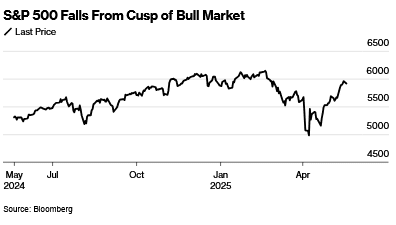

Wall Street got a rude awakening after the US downgrade by Moody’s Ratings, with stocks, bonds and the dollar falling amid renewed anxiety over the nation’s fiscal outlook at a time when there’s little clarity about the impacts of Donald Trump’s trade policy.

Following a torrid surge that put the S&P 500 on the brink of a bull market, the gauge fell about 1% on Monday. A selloff in big tech, which had led the equity rally from April’s lows weighed heavily on the market, with Tesla Inc. and Apple Inc. sliding at least 2.9%. Walmart Inc. slipped as Trump said the retailer should stop trying to blame tariffs as the reason for raising its prices.

Long-dated Treasuries, which had already been moving higher before Moody’s statement, topped 5% amid investor concerns about a surging debt load. The US deficit has been in excess of 6% of gross domestic product for the past two years, an unusually high burden outside of economic recessions or world wars. The greenback dropped against most of its global peers. Gold climbed.

“The US credit rating downgrade adds to a long list of uncertainties that the stock market is weighing right now, including tariff, fiscal, inflation and economic ones,” said Clark Geranen, chief market strategist at CalBay Investments.

The S&P 500 fell 0.7%. The Nasdaq 100 slid 0.8%. The Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped 0.4%.

The yield on 10-year Treasuries advanced four basis points to 4.52%. The Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index fell 0.5%.

“The Moody’s downgrade of the US debt was not a shocking development, but it’s not what the Treasury market needed given that it’s on the cusp of signaling an important change in trend for long-term interest rates,” said Matt Maley at Miller Tabak. He also noted that news came at a time when the stock market is “overbought and overvalued,” helping trigger the pullback.

The US government lost its last triple-A credit score from a major international ratings firm after a downgrade by Moody’s on May 16, citing more than a decade of inaction by successive US administrations and Congress to arrest a trend of large fiscal deficits.

And there’s concern the situation could get worse, with Republican lawmakers discussing a tax and spending package from Trump that critics say would add trillions more to the federal debt over the coming decade.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent downplayed concerns over the US’s government debt and the inflationary impact of tariffs on companies, saying the Trump administration is determined to lower federal spending and grow the economy.

Asked about the Moody’s Ratings downgrade of the country’s credit rating Friday during an interview on NBC’s Meet the Press with Kristen Welker, Bessent said, “Moody’s is a lagging indicator — that’s what everyone thinks of credit agencies.”

“We view this latest credit action as a headline risk rather than a fundamental shift for markets,” said Mark Haefele at UBS Global Wealth Management. “We would also expect the Federal Reserve to step in if there were a disorderly or unsustainable increase in bond yields. So while the downgrade may lean against some of the recent ‘good news’ momentum, we do not expect it to have a major direct impact on financial markets.”

Investors should buy any dips in US stocks fueled by Friday’s credit rating cut, as the trade truce with China has reduced the odds of a recession, according to Morgan Stanley’s Michael Wilson.

The strategist sees a greater chance of a pullback in equities after the downgrade

by Moody’s Ratings pushed 10-year bond yields above the key 4.5% level. However, “we would be buyers of such a dip,” Wilson wrote in a note.

“By our measures sentiment and positioning is still flashing an unambiguous contrarian buy signal,” said Max Kettner at HSBC. “We see a S&P 500 dip on Moody’s US downgrade as a potential opportunity.”

Thomas Lee at Fundstrat Global Advisors also views the Moody’s downgrade as a “largely non-event,” while adding that in case of any stock weakness, he would be “buying this dip aggressively.”

“There is no “surprise” here as Moody’s is citing facts we already know, the sizable US deficit,” Lee said. “And we doubt any major fixed income manager is surprised. There is simply no incremental information here.”

Meanwhile, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. strategist David Kostin said he expects the Magnificent Seven group of technology stocks to resume outperforming the broader S&P 500 on robust earnings trends. The cohort has slumped so far this year as investors dumped pricey US stocks.

Corporate Highlights:

- Nvidia Corp. Chief Executive Officer Jensen Huang outlined plans to let customers deploy rivals’ chips in data centers built around its technology, a move that acknowledges the growth of in-house semiconductor development by major clients from Microsoft Corp. to Amazon.com Inc.

- Nvidia Corp. and Abu Dhabi investment vehicle MGX are partnering with French firms to establish what they say will be Europe’s largest artificial intelligence data center campus, advancing French and Emirati ambitions in the field.

- Novavax Inc. jumped after US regulators fully approved its Covid vaccine, easing investors’ concerns after the clearance was delayed and US Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. raised doubts about its efficacy.

- US-traded shares of Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. slumped after a report that the Trump administration has raised concerns over Apple Inc.’s potential deal with the Chinese technology firm

- Bankrupt genetic-testing firm 23andMe agreed to sell its data bank, which once contained DNA samples from about 15 millio

- B. Riley Financial Inc. named Scott Yessner, who has been serving as a strategic adviser for the past two months, to succeed Chief Financial Officer Phillip Ahn as the company grapples with overdue regulatory filings and probes.

- Blackstone Infrastructure agreed to acquire New Mexico utility owner TXNM Energy Inc. for about $5.7 billion, the latest in a flurry of power deals as US electricity consumption grows.

Stocks

- The S&P 500 fell 0.7% as of 9:43 a.m. New York time

- The Nasdaq 100 fell 0.8%

- The Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 0.4%

- The Stoxx Europe 600 fell 0.4%

- The MSCI World Index fell 0.4%

- Bloomberg Magnificent 7 Total Return Index fell 1.2%

- The Russell 2000 Index fell 1.2%

Currencies

- The Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index fell 0.6%

- The euro rose 0.8% to $1.1254

- The British pound rose 0.7% to $1.3370

- The Japanese yen rose 0.5% to 144.98 per dollar

Cryptocurrencies

- Bitcoin fell 1% to $103,022.57

- Ether rose 1.5% to $2,431.05

Bonds

- The yield on 10-year Treasuries advanced four basis points to 4.52%

- Germany’s 10-year yield was little changed at 2.60%

- Britain’s 10-year yield advanced three basis points to 4.68%

Commodities

- West Texas Intermediate crude fell 0.5% to $62.20 a barrel

- Spot gold rose 0.8% to $3,230.84 an ounce

Read the full article HERE

Fed Chair Jerome Powell said interest rates may be higher in the long run due to risks from inflation and supply shocks

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell on Thursday said that the central bank’s framework for setting monetary policy may need to be adjusted to account for the possibility that supply shocks will become more common given the difficulties they pose for policymakers.

Powell delivered remarks at the Federal Reserve’s Thomas Laubach Research Conference and said that the central bank’s policy rate — the target range for the benchmark federal funds rate — could be higher in the future because of the potential for volatility with inflation and supply shocks occurring more often.

“Many estimates of the longer-run level of the policy rate have risen, including those in the summary of economic projections,” Powell said. “Higher real rates may also reflect the possibility that inflation could be more volatile going forward than during the inter-crisis period of the 2010s.”

“We may be entering a period of more frequent and potentially more persistent supply shocks — a difficult challenge for the economy and for central banks,” the chairman added.

Powell noted that the Fed’s policy rate is currently well above the “lower bound” of cutting the policy rate to zero — it currently sits at a range of 4.25% to 4.5% — and that the central bank has historically made significant cuts during times of recession.

“While our policy rate is currently well above the lower bound, in recent decades we have cut the rate by about 500 basis points when the economy is in recession. Although getting stuck at the lower bound is no longer the base case, it is only prudent that the framework continue to address that risk,” Powell said.

The Federal Reserve and other central banks face policymaking constraints when the policy rate is near zero, as it negates their ability to cut interest rates to stimulate the economy amid a downturn.

Powell also discussed how keeping longer-run inflation expectations anchored at the Fed’s 2% target will remain a key part of the Fed’s policymaking framework, saying that while some aspects of it “must evolve, some elements of it are timeless.”

“Since the Great Inflation, the U.S. economy has had three of its four longest expansions on record. Anchored expectations played a key role in facilitating these expansions. More recently, without that anchor, it would not have been possible to achieve a roughly 5 percentage point disinflation without a spike in unemployment,” Powell noted.

Read the full article HERE.

Retailer has weathered the trade war but says the full impact of tariffs on consumers has yet to come

Key Points

Walmart plans to raise prices this month and early this summer due to tariff-affected merchandise.

- Sales rose steadily as shoppers sought deals and fast shipping, but the trade war’s impact has yet to come.

- Walmart didn’t share a profit forecast for the current quarter and may absorb some tariff costs to keep prices lower.

Higher prices are coming to Walmart’s shelves.

The retailer said Thursday that it plans to raise prices this month and early this summer, passing along some of the cost as tariff-affected merchandise hits store shelves.

“The magnitude and speed at which these prices are coming to us is somewhat unprecedented in history,” Walmart Chief Financial Officer John David Rainey said in an interview. He said sales rose steadily in the latest quarter as shoppers flocked to deals and fast shipping, but the full impact of the trade war on consumers has yet to come.

“It’s a dynamic and fluid environment,” said Rainey. Walmart didn’t share a profit forecast for the current quarter because the company may absorb some tariff costs to keep prices lower than competitors, Rainey said.

Walmart is already raising some prices as its suppliers pass through higher costs. For example, tariffs drove up the price of bananas, one of the most frequently purchased items at Walmart, to 54 cents a pound, up from 50 cents, he said.

Earlier this week, the U.S. agreed to temporarily lower tariffs on Chinese imports to 30% from 145%. A 30% tariff on Chinese goods is better than 145%, but still means a meaningful price increase for most consumers, Rainey said.

In March and April, stock markets gyrated and consumer sentiment plummeted, but Walmart’s sales grew. The company’s U.S. comparable sales, those from stores and digital channels operating for at least 12 months, rose 4.5% in the three months ended May 2, beating investors’ expectations.

Unlike many other companies, Walmart left its sales and profit forecasts for the full year unchanged. Previously Walmart had set cautious expectations for its financial performance this year, in part because of the unpredictability of tariffs. Walmart is likely to be a relative winner in a time of economic uncertainty, Rainey said. “We tend to gain share, come out stronger.”

Walmart shares rose around 2% in premarket trading.

Walmart grew steadily through the pandemic and the period of steep inflation that followed. The Trump administration’s on-and-off-again tariffs have created a new challenge for retailers. Some of those impacts have yet to hit retailers’ shelves, in part because many companies stockpiled goods ahead of the tariffs or postponed shipments from China. So far, the economic impact of tariffs has been muted in the U.S., with unemployment and inflation holding steady.

Walmart said its consumers in the latest quarter continued to shop cautiously, as they have for the past few years because of inflation on essentials such as groceries and child care. That has been a boon to Walmart.

Walmart Thursday said more high-income households in the U.S. chose the retailer for groceries, and shoppers embraced its low-price store brand and “rollbacks,” or temporary deals. Overall inflation ticked slightly higher in the latest quarter, primarily due to the price of eggs, the company said. Walmart’s global e-commerce business grew 22% in the quarter.

Read the full article HERE.

When and how much prices will rise depends on the product, and on the ripple effects of the tariff regime, said Paul Donovan, chief economist at UBS Global Wealth Management.

President Donald Trump’s tariffs are already increasing prices on consumer goods. More price hikes could be ahead. But when and how much prices will rise depends on the product and the knock-on effects of the tariff regime, Paul Donovan, chief economist at UBS Global Wealth Management, said Wednesday. Of course, it also depends on how long the tariffs stay in place and at what level, which is in flux.

Trump’s announced levies on trade so far have cumulatively lifted the effective tariff rate to roughly 25% from 2.5% at the start of the year, but are expected to be negotiated down from here. Donovan estimates that a 10% increase in tariffs could raise price levels by about 1.1%. He doesn’t expect companies would raise prices gradually over time, but would instead opt for one-time increases to compensate for the hit to their profits.

However, second order effects, including price-led inflation, could persist at the retail level, he said on the call with members of the media. “If consumers believe prices are increasing, then retailers can push through price increases because their customers are expecting it as a concept.”

The behavioral component, meaning how businesses and consumers react to both price hikes and the anticipation of further increases, makes it hard to judge risks, he said.

Delayed impact. The impacts will begin showing up in economic releases in the coming weeks, Donovan said. “On average I would expect something to show up in June price inflation data,” he said. “But the perception is already shifting.”

When prices move depends on product shelf life, which varies widely, and that affects how soon companies have to react to tariffs. Some companies stockpiled inventory in advance of tariffs. Many consumer items are shipped overseas and the supply chain takes weeks. In contrast, “The life span of a head of lettuce is a matter of days,” Donovan said.

Donovan notes that recent consumer surveys show higher inflation expectations and a gloomy economic outlook. Some surveys also show a partisan split with Democrats and independents anticipating higher rates of inflation than their Republican peers.

The University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index for April showed that Americans anticipate inflation for the year ahead to jump to 6.5%. That’s the highest reading since 1981.

Donovan said that he doesn’t expect tariffs to remain at significant levels for a prolonged period, but if they did, the impact would be initially inflationary, but then disinflationary because economic growth would slow.

Federal budget impact. While tariffs, like other tax increases, will increase revenue to the U.S. government, the impact on consumer prices may be larger than the benefit to federal coffers, Goldman Sachs economists explain.

“[P]rohibitively high tariff rates on imports from China will shift import demand away from China toward countries with higher production costs but lower U.S. tariff rates,” Goldman Sachs researchers led by Chief Economist Jan Hatzius wrote in a May 7 note. “This was true in the last trade war as well, but the tariff differential is now vastly larger—145% for China versus just 10% for most other countries. That shift will also raise U.S. prices, but without a commensurate increase in the effective tariff rate.”

Economic outlook weakens. Worsening economic forecasts by many Wall Street economists are a sharp contrast to the beginning of the year when the economy was on strong footing, inflation had declined substantially, and businesses were projecting confidence about economic expansion.

Some companies have already begun raising prices. For instance, Ford Motor is increasing prices on several 2025 models, Microsoft is increasing Xbox prices, and Mattel has indicated toy prices will go up. Several luxury brands have announced they would be hiking prices.

Other companies, even those not directly affected by tariffs, have suspended earnings guidance due to the significant economic uncertainty wrought by trade policy changes. For example, Southwest Airlines, American Airlines and Alaska Air pulled their 2025 guidance.

Read the full article HERE.