US trade policy may create an epic buying opportunity, but much later if there is a downturn.

Recession

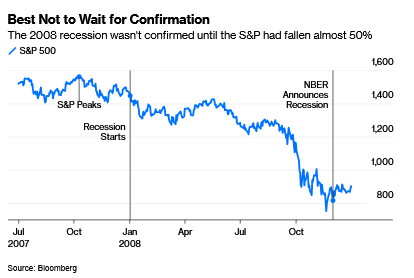

When you think a recession is coming, it generally pays to sell first and ask questions later. Waiting for confirmation that the economy is declining is just too costly. For a spectacular demonstration, look to the events of 2008, when the National Bureau of Economic Research announced that a recession had started in January of that year — but didn’t announce this until December:

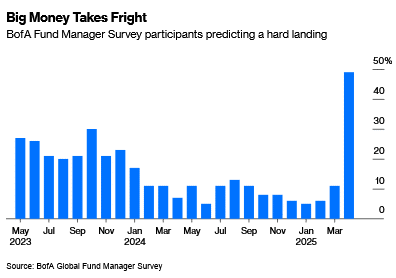

From the start of the recession to the NBER’s acknowledgement, the S&P 500 almost halved. It was better to take a judgment first. That’s why there’s particular interest in the latest survey of global fund managers by Bank of America Corp., the first since the “Liberation Day” tariffs announcement, which showed a dramatic increase in fears of an economic hard landing:

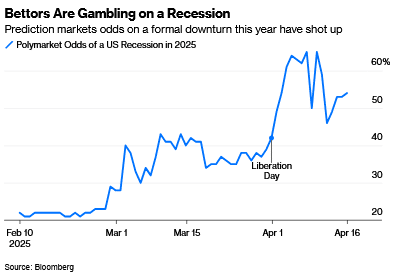

If big fund managers take fright, then their actions can guarantee a market selloff as they move their money to safety. And they’re not the only ones growing much more nervous. Odds of a recession this year have ballooned on the Polymarket betting site, and now stand at more than 50%:

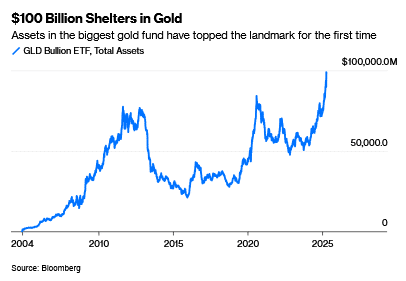

Traditional indicators of market negativity show a similar trend. The total assets of State Street Global Advisors’ GLD exchange-traded fund, the biggest fund for retail investors to buy gold, topped $100 billion for the first time Wednesday, as a rising price and growing interest from small investors combined:

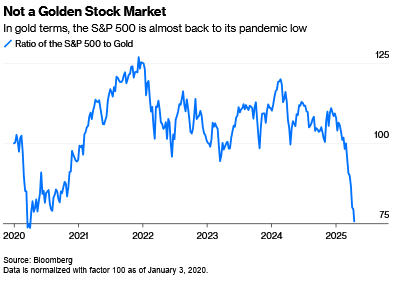

(Parenthetically, the gold rally provides vital context for the stock market. The ratio of the S&P 500 to the gold price, which effectively prices the index in gold rather than dollars, has tanked this year and is almost back to its pandemic-era low. If you choose to view the post-Covid rally as one big side effect of cheap money, this would tend to support you.)

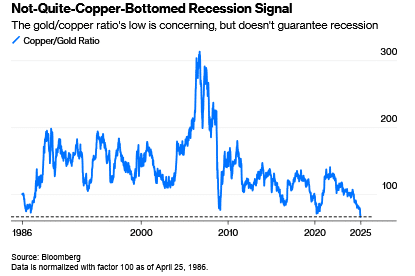

Combining gold with copper provides another alarming recession signal. The former rises when people are worried, while a gain in the latter shows that economic activity is expanding. So when copper drops to its lowest in gold terms in at least 38 years, that’s concerning (although it’s worth noting that the previous low in 1987 didn’t prefigure a recession):

There’s another problem with making a confident recession prediction. Formerly reliable market indicators have been foretelling one for so long without success that it’s getting harder to take them seriously. The New York Fed recession probability indicator is based on the bond yield curve. Over time, an inverted curve, in which long bonds yield less than shorter-term instruments, has been a surefire sign of trouble ahead. But it’s never been more confident of an oncoming recession than it was in 2022, and so far it hasn’t come to pass:

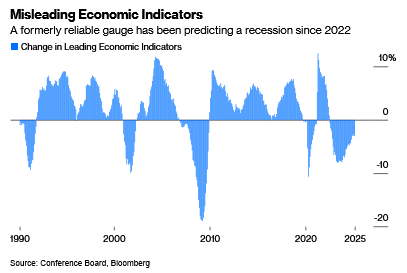

Another virtually foolproof signal comes from the Conference Board’s Leading Economic Indicators, which smooshes together various measures of the economy and market. Just like the yield curve, it successfully predicted the last four recessions, but also a fifth that still hasn’t happened:

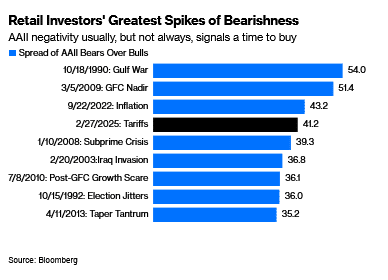

One problem with getting out of the market when everyone is scared of a recession is that this is often a great contrarian time to buy. The American Association of Individual Investors has for decades asked its members a weekly question: Are you bullish or bearish? The recent peak in the majority of bears over bulls makes this the fourth-biggest incidence of bearishness since 1987. Here it is in context:

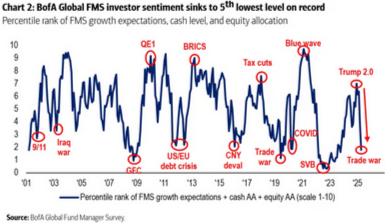

All were either good or great times to buy, with the significant exception of the angst over subprime bankruptcies in January 2008, when a few months later investors discovered they hadn’t seen nothing yet. Similarly, BofA has a measure of sentiment based on how much cash fund managers are holding, their hopes for growth, and the amount they’ve allocated to equities. With the exception of the response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001, all the previous times when sentiment dropped this low proved decent times to buy:

A further problem: The recession fears this time around have been driven entirely by a new policy (US tariffs) that might yet be revoked. The chances are that it will create an epic buying opportunity at some point in the future. But that time to buy will come much later if there is a recession. While the uncertainty over tariffs persists, it will be hard to put together a market rally.

Words, Words, Words

It’s conventional wisdom that deeds matter more than words. That buttresses the continuing optimism over trade policy: For all his protectionist invective, Donald Trump has announced delays or retreats on most of his tariffs.

There are exceptions. The Federal Reserve often uses the power of the jawbone and what it says matters a lot. If people react to a warning, the Fed can even have its desired effect without needing to do anything. Because central bankers have to mind their words, mere choice of subject can be most significant.

For a prime example, Fed Chair Jerome Powell triggered a big afternoon selloff by talking frankly — but without saying anything anyone didn’t know — in a discussion at the Economics Club of Chicago. He admitted that there “isn’t a modern experience for how to think about this:”

Our obligation is to keep longer-term inflation expectations well-anchored and to make certain that a one-time increase in the price level does not become an ongoing inflation problem. We may find ourselves in the challenging scenario in which our dual-mandate goals are in tension

More or less everyone is alive to the risk that tariffs could both raise inflation and lower growth, and hammer both sides of the Fed’s mandate. The fact that Powell said so, however, along with the explicit assertion that higher prices due to tariffs might push up inflation expectations, was a sign that he wouldn’t resort to rate cuts at the first sign of trouble. He might easily have dropped such a hint — and many traders were furious with him for not doing so.

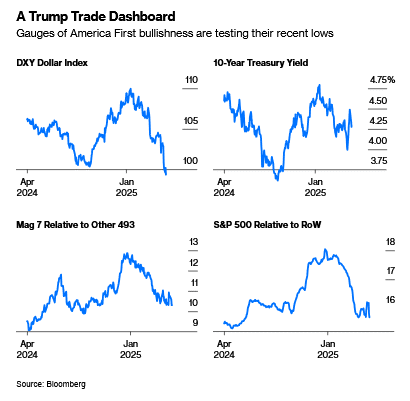

Equities, led by Big Tech, sold off after he spoke, as did the dollar. Amid much excitement, the main elements of US exceptionalism, are back to testing their post-“Liberation Day” lows — but at least Treasury yields are falling again:

Central bankers’ mere words do indeed matter. But do we need to note what politicians are saying? Normally, their deeds matter far more. There have been exceptions of late, however, particularly when coming from the mouth of US Vice-President J.D. Vance.

In February, he made an epochal speech in Munich, lacing in to European leaders to say that they were more threatening than Vladimir Putin’s Russia. Two weeks later, there was his equally famous berating of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy in the Oval Office. Nobody was hurt in these exchanges, but they had consequences.

After the Vance speech, Points of Return was headlined “There’s No Template for the Shock Europe Just Got” and described it as a major geopolitical event. That prompted some pushback from the US. One reader said that the column had taken on a “tilt” and added:

The intransigency of the European state appears to require strong rhetoric to even dent their narrative. They are words, Europe is overdue to act.

That’s a reasonable response, but not to the message that Vance actually delivered. He didn’t read the riot act over defense spending — which would have been reasonable — but made such a wide-ranging attack on Europe and all it stood for that his listeners decided the US could no longer be trusted as an ally. The subsequent boost to defense spending in Germany isn’t to make sure it keeps its NATO commitments, but to ensure its independence from the US. And as we’ve written at length, that’s had massive financial impacts.

The Munich speech is only the biggest example. People don’t like being insulted and hate criticism from foreigners. Describing the Chinese as peasants gifted propaganda to the US’ prime trade adversary, and helped it to muster support in its population. It’s now a Chinese condition of talks that the US shows respect, which is fair enough. If you want to make a deal with someone, don’t insult them first.

Vance’s response to the British and French proposal to send peacekeeping troops to Ukraine — dismissing the efforts of “some random country that hasn’t fought a war in thirty of forty years” — led to a furious response, particularly from his more natural supporters on the right, who have also noted that US conservatives are criticizing Winston Churchill. UK forces fought alongside the US in Kuwait, Afghanistan and Iraq. This came across as a specious insult, impeding US aims to get Europe’s powers to step forward in their own defense.

The administration has as yet done nothing to back up its interest in seizing Greenland, but Vance’s trip there appeared designed to create the greatest possible insult. Denmark’s people already felt grievously affronted. And while the Trump administration wants to add Canada as a state, the leadership’s deliberately offensive words have triggered an economic backlash.

It’s harder to grasp this from the US, but this language has done lasting self-harm. As my old colleague Katie Martin pointed out in the Financial Times, trust is lost, and the US is now open to ridicule.

It’s not often that mere words do matter. But US discourse has been so aggressive and offensive as to sunder long-lasting alliances, and forestall the possibility of a rapprochement.

Survival Tips

Happy Easter. Points of Return will be taking off for Good Friday, but for some great Easter-themed music, I recommend Puccini’s Stabat Mater, a setting of the words of Mary watching her son on the cross, conducted here with fire in his eyes by the great Carlo Maria Giulini. It’s a tad too operatic for some tastes, but it’s wonderful. Or you could try Jesus Christ Superstar, a true rock opera, in which Judas gets the best lines and stands in for doubting modern agnostics. It’s more than 50 years old and its stature grows with time. Have a great weekend everyone.

Read the full article HERE.