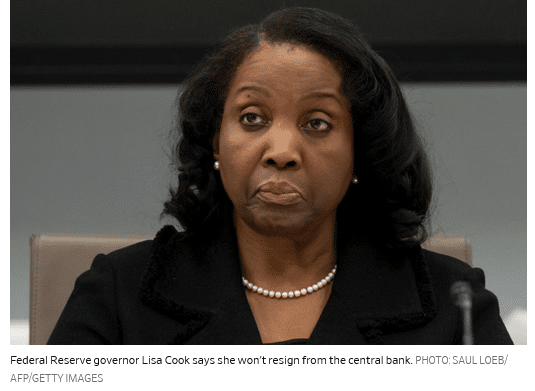

Move to fire Federal Reserve governor Lisa Cook comes after the Supreme Court signaled intention to protect central bank’s independence

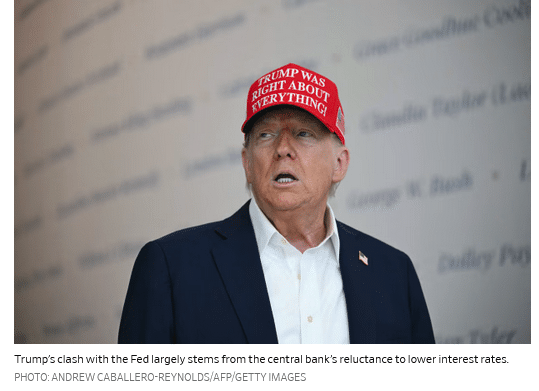

President Trump is pushing his drive for unilateral control of the U.S. government to new levels as he seeks to fire Federal Reserve governor Lisa Cook, potentially crossing a red line the Supreme Court has suggested protects the central bank from direct political manipulation.

Since taking office, Trump repeatedly has taken aim at federal laws protecting a range of government officials from arbitrary dismissal, firing without cause Democratic appointees serving fixed terms to supervise agencies that oversee consumer safety, labor organizing, fair-trade practices and the integrity of the civil service, among others.

In a Monday letter published on social media, Trump told Cook that unproven allegations of mortgage fraud were sufficient cause for dismissal.

Cook, a Biden administration appointee, has vowed to fight Trump’s action. “President Trump purported to fire me ‘for cause’ when no cause exists under the law, and he has no authority to do so,” she said in a Tuesday statement. “I will not resign. I will continue to carry out my duties to help the American economy as I have been doing since 2022,” she said. Her lawyer, Abbe Lowell, said he would file suit, setting up a case likely to reach the Supreme Court.

In a statement Tuesday, the Federal Reserve said the governors’ lengthy terms and tenure protection “serve as a vital safeguard, ensuring that monetary policy decisions are based on data, economic analysis, and the long-term interests of the American people.”

The statement said the Fed would obey any court decision concerning Cook’s “ability to continue to fulfill her responsibilities as a Senate-confirmed member.”

Robert Post, a Yale law professor, said the stakes could hardly be higher.

“Everyone agrees that if a Fed governor is taking a bribe, they should be removed. It’s not controversial. So the question is, What is cause?” he said.

If courts permit Trump to remove Cook based only on his say-so, rather than requiring proof of wrongdoing, then the for-cause protection is meaningless, Post said.

In Cook’s case, Bill Pulte, a Trump appointee who leads the Federal Housing Finance Agency, publicized the mortgage allegations and referred them to the Justice Department. But Cook hasn’t been charged with any civil or criminal violation.

The Federal Reserve Act, first adopted in 1913, provides 14-year terms for Fed governors, “unless sooner removed for cause by the President.” The statute doesn’t define cause, but laws establishing other independent agencies typically refer to neglect of duty, inefficiency or malfeasance as grounds for removal.

In 1912, President William Howard Taft dismissed two members of a federal board after an investigatory committee he appointed determined the officials had engaged in self-dealing, according to a 2018 law-review article by a University of Virginia law professor, Aditya Bamzai. Only one other president has removed a tenure-protected official for cause, Bamzai wrote: Richard Nixon, who in 1969 cited unspecified reasons to dismiss Fannie Mae head Raymond Lapin, a Lyndon Johnson appointee. Lapin didn’t pursue a legal challenge.

Behind today’s fight is Trump’s frustration at the Fed’s reluctance to cut interest rates, which could provide a temporary jolt to an economy that has seen little improvement under the president’s hand. Cook’s removal would create a vacancy allowing Trump to appoint a majority of governors.

Several other officials fired by Trump have sued to challenge their dismissals, quickly winning a series of early court orders allowing them to keep their jobs, at least temporarily. Judges cited longstanding Supreme Court precedent limiting the executive’s authority to remove independent agency officials without good cause. But in a pair of orders this spring, the high court itself has allowed Trump to dismiss the officials for now and suggested a readiness to reconsider a 90-year-old decision that limits presidential removal authority.

A May order approved the removal of Biden appointees from the National Labor Relations Board and the Merit Systems Protection Board. But the unsigned opinion from the court’s conservative majority signaled it would apply a different test for the Fed, by far the most powerful independent agency created by Congress. “The Federal Reserve is a uniquely structured, quasi-private entity” with a “distinct historical tradition,” the court said.

In dissent, Justice Elena Kagan suggested the majority had crafted “a bespoke Federal Reserve exception” to its likely expansion of presidential authority.

The central bank’s “independence rests on the same constitutional and analytic foundations as that of the NLRB, MSPB, FTC, FCC, and so on,” Kagan wrote, joined by fellow liberal justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson.

Some scholars agree that the court will have a tough time finding a clear distinction that shields the Fed from presidential interference while granting Trump nearly unfettered power to dismiss all other federal officers.

“The Federal Reserve is not just a bank. It has tremendous regulatory authority,” said Ilan Wurman, a law professor at the University of Minnesota. “There is no executive power exception for financial regulators, and never has been.”

Independent agencies date from the 1880s, when the complexities of an expanding industrial economy led Congress to create a nonpartisan civil service and a class of expert bureaus characterized by a degree of bipartisanship and a measure of autonomy from each presidential administration.

A 1935 Supreme Court decision known as Humphrey’s Executor upheld that structure, which supporters argue promotes the public interest by partially insulating some policy decisions from political pressure and assuring some continuity regardless of shifting partisan majorities.

Some conservatives have argued that the Constitution places an indivisible executive power in the president himself—and that Congress has no right to abridge that authority by shielding appointed officials from removal at the president’s pleasure. That theory of a “unitary” executive branch gained currency in the Reagan and Bush eras and now appears to command a majority of the Supreme Court. Although it has yet to overrule Humphrey’s Executor fully, the writing is on the wall.

In June, the court granted Trump’s emergency request to fire three Biden appointees to the Consumer Product Safety Commission, overturning lower courts that sided with the commissioners under the 1935 precedent.

The unsigned opinion repeated the finding the court had made in May: The Trump administration “faces greater risk of harm from an order allowing a removed officer to continue exercising the executive power than a wrongfully removed officer faces from being unable to perform her statutory duty.”

Read the full article HERE.