When investors are wildly optimistic, it is much harder for the market to rise and much easier for it to fall on any hint that they might be wrong

The market feels toppy. There is no science to this and readers will have to judge for themselves. But here are a bunch of things that make me think trouble might be imminent for stocks—perhaps a correction, perhaps the start of something bigger, but at least a bump in the road.

Bulls are everywhere. Bears are hard to find. This shows up in sentiment, in surveys and in the capitulation of the permabears.

Sentiment is euphoric, according to Citigroup’s Levkovich indicator. This index combines lots of measures and suggests investors have only been more positive twice, in the postpandemic SPAC/cannabis/green bubble and in the dot-com bubble of 1999-2000.

When investors are wildly optimistic, it is much harder for the market to rise—everyone’s already got a lot of stocks—and much easier for it to fall on any hint that they might be wrong. I don’t know what the trigger might be, but it doesn’t need to be much.

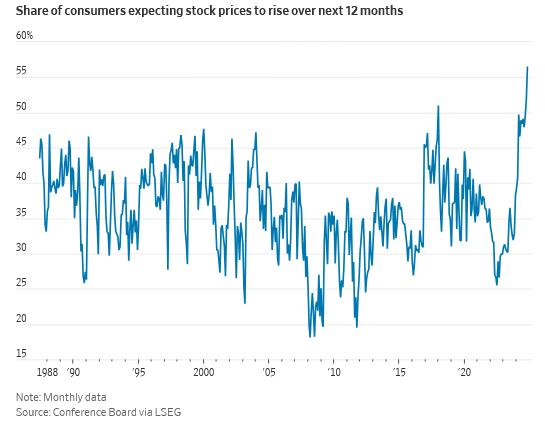

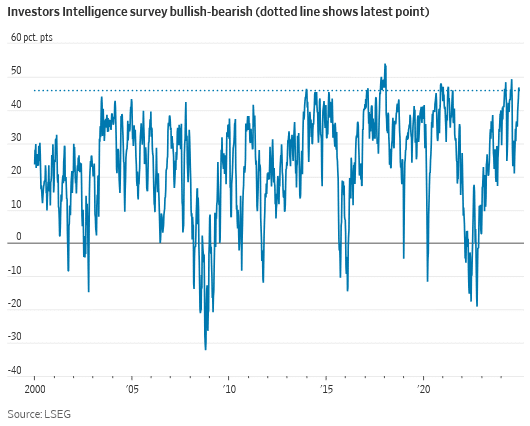

Other signs of optimism. Investment newsletter writers have rarely been more bullish or less bearish, according to the weekly survey by Investors Intelligence. Households have never been so confident that stocks will rise over the next year, according to the Conference Board’s monthly survey.

And fund managers shifted after the election to be more overweight U.S. stocks than any time since 2013, pretty much as all-in on the U.S. as they have ever been, according to Bank of America’s survey. Money is pouring into funds at an exceptionally high rate too, close to new highs.

Some of the best-known bears have given up. Economist and fund manager Nouriel Roubini used to revel in the moniker of “Dr. Doom,” but he told Bloomberg TV “I’m not Dr. Doom, I’m Dr. Realist,” while talking up the prospects for the U.S. economy. David Rosenberg of Rosenberg Research didn’t actually say the fateful words “this time is different” but he did write that “traditional valuations, at the least, are not that helpful right now.”

This time will be different. Rosenberg thinks investors have shifted away from the standard metric of price against one-year forward earnings to look further out, because of the prospects for an AI-driven productivity boom. Even those who think markets will eventually return to something like normal, such as Goldman Sachs, don’t expect issues soon.

Almost everyone agrees AI and the U.S. economy are great. Wei Li, chief investment strategist of the BlackRock Investment Institute, says spending on artificial intelligence will be “of a magnitude similar to previous industrial revolutions, but happening so much faster.” She argues that “U.S. exceptionalism has been years in the making.”

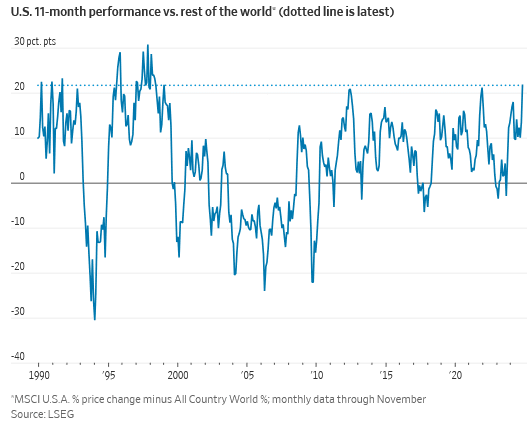

The widespread agreement shows up in prices. The biggest AI-linked stocks dominated the market this year, while the U.S. market outperformed the rest of the world by almost 22 percentage points in the year to the end of November, the most over an 11-month period since 1998.

No one cares about valuation. It isn’t just that people think AI and the U.S. will do well. They don’t seem to care about the price, even though price is the starting point for future returns. Cheap, or value, stocks have been underperforming for years, but just had their longest-ever consecutive daily decline, falling every day for the past 11 days. These are almost by definition bad companies, but the disconnect from the excitement about growth stocks is extreme.

The same goes for stocks against bonds, with the earnings yield—the inverse of the PE ratio—barely above the 10-year Treasury yield, the lowest reward on this measure for the risk of holding stocks since the aftermath of the dot-com bubble. It isn’t just that people want to buy good companies, they seem to want them at any price.

Inside trades. The one group not buying into the story are corporate executives, who ought to be best-placed to see the potential for a new golden era for American profits. They have been selling more stock than they buy, according to regulatory filings, suggesting they think prices are too high.

None of these points are proof that the market must fall, let alone that it will happen soon. None have a perfect record and on some measures—such as the American Association of Individual Investors’s survey—things aren’t so extreme. But I don’t want to be part of a crowd buying into a narrow story when prices, valuations and hope are already extremely high, and insiders aren’t willing to back it with their money.

This feels like a good time to take some money off the table.

Read the full article HERE.