Two months before Black Monday, the market crash that led to the Great Depression, a Massachusetts economist named Roger Babson, fretting over a wave of mom-and-pop investors borrowing money to buy stocks, declared in a speech that “sooner or later a crash is coming and it may be terrific.” Afterward, the market sank 3%, a dip known at the time as the “Babson Break.” But in the weeks that followed, writes Andrew Ross Sorkin in his engrossing new history, 1929: Inside the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History—and How It Shattered a Nation, “the market shook off Babson’s foreboding,” in part because of optimism over new mass-market products like the radio and the automobile. “Investors with an ‘imagination’ were winning again.”

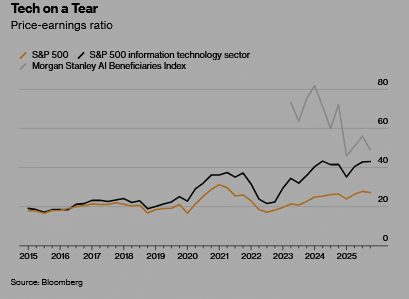

Today there are many Cassandras like Babson warning about AI, in particular the valuation of public and private technology companies and their headlong pursuit of the elusive goal of artificial general intelligence (systems that can do just about anything a human can do and more). Tech companies are on pace to spend just shy of $1.6 trillion annually on data centers by 2030, according to data analyst Omdia. The magnitude of the hype around AI, whose prospects as a profit maker remain entirely hypothetical, has confounded many sober-minded investors. Yet now, as a century ago, the idea of missing out on the next big thing has persuaded many companies to ignore such prophecies of doom. They “are all kind of playing a game of Mad Libs where they think these moonshot technologies will solve any existing problem,” says Advait Arun, a climate finance and energy infrastructure analyst at the Center for Public Enterprise, whose recent Babsonesque report, Bubble or Nothing, questioned the financing schemes behind data center projects. “We are definitely still in the irrational exuberance stage.”

Journalists usually would be wise to abstain from debating whether a resource or technology is overvalued. I have no strong opinion on whether we’re in an AI bubble, but I wonder if the question may be too narrow. If you define a speculative bubble as any phenomenon where the worth of a certain asset rises unsustainably beyond a definable fundamental value, then bubbles are pretty much everywhere you look. And they seem to be inflating and deflating in lockstep.

There may be a bubble in gold, whose price has soared almost 64% in the year to Dec. 12, and one in government debt, according to Børge Brende, chief executive officer of the World Economic Forum, who recently observed that nations collectively haven’t operated this deeply in the red since World War II. Many financiers believe there’s a bubble in private credit, the $3 trillion market in loans by large investment houses (many for the purpose of building AI data centers) that’s outside the heavily regulated commercial banking system. Jeffrey Gundlach, founder and CEO of money-management firm DoubleLine Capital, recently called this opaque, unregulated free-for-all “garbage lending” on the Bloomberg podcast Odd Lots. Jamie Dimon, JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s CEO, dubbed it “a recipe for a financial crisis.”

The most obvious absurdities have materialized, where there’s no easy way to judge an asset’s intrinsic worth. The total market value of Bitcoin, for example, rose $636 billion from the start of the year through Oct. 6—before losing all of that and more, as of Dec. 12. The trading volume of memecoins, those virtual contrivances that commemorate online trends, peaked at $170 billion in January, according to crypto media firm Blockworks, but by September had collapsed to $19 billion. Leading the decline were the $TRUMP and $MELANIA coins, launched by the first family two days before Inauguration Day, which have lost 88% and 99% of their worth, respectively, since Jan. 19.

Many investors evaluated these crypto currencies not for their potential to create underlying value for shareholders and the world—the way they might for a stock in a conventional company that reports earnings, for example—but more narrowly for the chance to make a lot of money quickly. They approached it a little like they would sidling up to the craps table on a trip to Las Vegas.

There might be demographic reasons that investors, particularly those drawn to crypto, sports gambling and online prediction markets, are trying to game financial markets as if they were casinos. According to a recent Harris poll, 6 in 10 Americans now aspire to accumulate extreme wealth. Seventy percent of Gen Z and millennial respondents say they want to become billionaires, versus 51% of Gen Xers and boomers. A study last year by the financial firm Empower suggested that Zoomers believe that “financial success” requires a salary of nearly $600,000 and a net worth of $10 million.

Thanks to TikTok videos, group chats, Reddit boards and the instantaneous and unavoidable nature of the internet, everyone in the world is now apprised of moneymaking opportunities at the same time. That sounds fine in principle but has led to a frenzy of imitation, mass competition and hive-mind behavior that makes the new Apple TV show Pluribus look timely. The traditional economy, with its complicated and infinitely varied dimensions, has been supplanted by the attention economy—the things we’re all, everywhere, obsessing about at any particular time.

In the business world, that singular focus is on AI. In popular culture there was a Sydney Sweeney bubble, which followed a Pedro Pascal bubble, and a “6-7” bubble. (If you don’t have teens, just Google it.) Over the past year, thanks to celebrities such as Lisa from the K-pop band Blackpink, we also have a worldwide mania over the cute but worthless zoomorphic stuffies sold by Chinese toymaker Pop Mart International Group. Call it the Labubble.

In food there’s most certainly a protein bubble, with everyone from the makers of popcorn to breakfast cereal marketing their protein content to appeal to health-conscious consumers and GLP-1 users. In media there just might be a bubble in Substack newsletters, celebrity-hosted podcasts (Amy Poehler’s Good Hang and Meghan Markle’s Confessions of a Female Founder) and celebrity-focused documentary biopics authorized by their subjects and available to stream nearly every week (the latest on Netflix: Being Eddie on Eddie Murphy, and Victoria Beckham). “Everyone’s reference group is global and goes far beyond what they can see around them and beyond what their actual class or position is,” says W. David Marx, the author of Blank Space: A Cultural History of the Twenty-First Century. “You can have globally aligned movements within these markets that in the past would have been impossible.”

The stakes are higher for AI than they are for Labubus, of course. No company wants to be left behind, and so every major player is plowing forward, building computing infrastructure using complex financing arrangements. In some cases this involves a special purpose vehicle (remember those from the 2008 financial crash?) loaded with debt to buy Nvidia Corp. graphics processors, the AI chips that some observers think may depreciate more quickly than expected.

The tech giants can weather any fallout from this FOMO-induced stampede. They’re paying for their data centers largely from their robust balance sheets and can navigate the consequences if white-collar workers all decide that, say, the current version of ChatGPT is plenty good enough to craft their annual self-evaluation. But other companies are engaging in riskier behavior. Oracle Corp., a stodgy database provider and an unlikely challenger in the AI rush, is raising $38 billion in debt to build data centers in Texas and Wisconsin.

Other so-called neoclouds, relatively young companies such as CoreWeave Inc. and Fluidstack Ltd. building specialized data centers for AI, Bitcoin mining and other purposes, are also borrowing heavily. Suddenly the cumulative impact of an AI bubble begins to look more severe. “When we have entities building tens of billions worth of data centers based on borrowed money without real customers, that is when I start worrying,” says Gil Luria, managing director at investment firm D.A. Davidson & Co., evoking Roger Babson from a century ago. “Lending money to a speculative investment is never a good idea.”

Carlota Perez, a British-Venezuelan researcher who’s been writing about economic boom and bust cycles for decades, is concerned as well. She says innovation in tech is being turned into high-stakes speculation in a casino economy that’s overleveraged, fragile and prone to bubbles ready to pop as soon as active doubt begins to spread. “If AI and crypto were to crash, they are likely to trigger a global collapse of unimaginable proportions,” she wrote in an email. “Historically, it is only when finance suffers the consequences of its own behavior, instead of being perpetually bailed out, and when society reins it in with proper regulation, that truly productive golden ages ensue.” Until then, hold your Labubus tightly.

Read the full article HERE.