US and European companies are frontloading orders and weighing price hikes while Chinese factories hunt for buyers elsewhere

A two-hour drive west of Shanghai, Sunny Hu has spent almost two months since the US election rushing shipments of her company’s outdoor furniture and pavilions to American customers and racing to diversify Hangzhou Skytech Outdoor Co. Ltd. into other markets.

Meanwhile, in the heart of Germany’s Riesling belt, eighth-generation winemaker Matthias Arnold has been fielding an influx of special orders from US importers since Donald Trump’s victory. He’s rushing to fill as many as possible before the president-elect can bring back levies on European wines that he imposed in 2019 but the Biden administration suspended.

Across the world, businesses aren’t waiting until US Inauguration Day on Jan. 20 to see which countries, products or tariff rates are announced in Trump’s widely telegraphed trade wars. The mere threat of his universal tariffs is sparking a scramble that’s leaving the global trading system prone to bottlenecks, saddled with higher costs and vulnerable to disruptions should an economic shock come along.

“We’re still in the freakout period,” said Robert Krieger, president of Los Angeles-based customs brokerage and logistics advisory firm Krieger Worldwide. “There’s about to be a king tide in the supply chain.”

At California-based JLab, Chief Executive Officer Win Cramer had already shifted his supply chains away from China to dodge tariffs imposed during Trump’s first presidency. Along with a hiring freeze imposed until June amid the uncertainty, his next move would be raising prices for the company’s headphones and wireless products if a universal tariff is applied this time around.

To get ahead of the game, some firms are frontloading orders. Others are seeking new suppliers or, if that’s not possible, renegotiating terms with existing ones. A common theme: The renewed stress comes with higher costs, in the form of bigger inventories, costlier expedited shipping, or taking a chance on untested partners. Profits will suffer and expenses will be reduced elsewhere, they said. Ultimately consumers will foot the bill.

The problem is, for all the preemptive moves, there’s no guarantee that the strategies that helped some businesses endure Trump’s first trade war will work this time around. As shown by Trump’s late November threat to impose additional 10% tariffs on goods from China and 25% tariffs on all products from Mexico and Canada, both allies and adversaries are in his sights this time around.

Zipfox, an online product-sourcing platform that links US-based businesses with factories primarily in Mexico, has seen a 30% uptick in quote requests and new buyer signups since two weeks before the election, according to founder and CEO Raine Mahdi, who said inquiries spiked again after Trump threatened 100% tariffs on BRICS nations. Most of those are from importers of goods manufactured in China. Mahdi warns against complacency.

“If you wait too long, you’re going to find yourself trying to make the transition in a pinch,” Mahdi said. “This time you’re not catching the tail end of the Trump administration, you’re catching the entire thing and with a new wrath.”

The survival instincts of business leaders are already beginning to show up in high-frequency data, and central bankers are keeping a close eye given the threat that higher import taxes pose to their inflation fights.

China’s ports saw double-digit growth in container throughput in the two weeks around the election and that rose further to an almost 30% gain in the second week of December. International air freight flights have increased by at least a third each week since mid-October and economists expect that’ll continue as customers rush to frontload orders.

Across the Pacific, the busiest container gateway in the US, made up of the twin ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, is seeing a surge of inbound shipments — not unlike the wave that accompanied Trump’s first tariff volleys at China. Both ports smashed pandemic-era records in the third quarter and volumes are expected to stay elevated into next year.

The advanced ordering started well before the US election in early November and is showing up at the docks now. At the Port of LA alone, inbound container shipments in November jumped 19% from the same period a year earlier, and 2024 is on track to be Long Beach’s busiest year ever. But the cargo crush through Southern California is unlikely to last for long and probably means a slump at some later stage.

“The surge in imports nationwide could continue into the spring of 2025,” Port of Long Beach CEO Mario Cordero told reporters in December. “Back in 2018, tariffs initiated during the first Trump administration resulted in a 20% decrease in imports from China and a 45% decrease in exports to China due to retaliatory actions.”

Tariffs aren’t the only factor at play given the typical rush ahead of China’s annual Lunar New Year holiday, which starts in late January, and the need to get ahead of potential port strikes in the US. Given that backdrop, it wouldn’t take a lot to stoke additional pressure in the global trading system, said Citigroup Inc. senior global economist Robert Sockin.

“Shipping costs may feel additional upward pressure if front-running activity picks up notably,” he said. “If front-running is particularly extensive, it could create some bottlenecks at US ports which would exacerbate supply chain pressures.” Prospects for another dockworkers’ strike just days before Trump’s inauguration only compound those concerns.

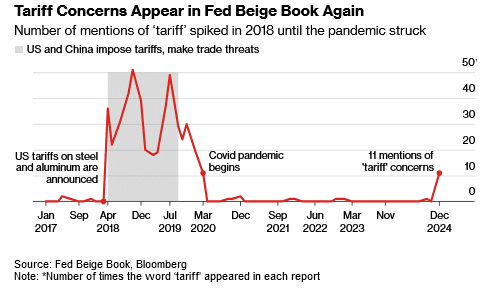

Since the US election in early November, the Federal Reserve has heard more concerns about the levies. The word “tariff” appeared 11 times — — the most since 2020 — in its latest Beige Book report, a regional survey of businesses.

An analysis of earnings-call transcripts to count mentions of tariffs by executives of S&P 500 companies jumped in November to the highest in records going back to late 2019, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Industrial firms and in particular industrial machinery and suppliers are talking about tariffs the most.

Smaller companies are doing more than talking, though it’s too soon to measure with any precision the extent of the economic fallout.

If Lynlee Brown’s email inbox is any guide, the impact will be widespread. She’s a global trade partner at EY, the consulting giant. In the early morning hours after the US election, she had received more than 400 messages. The queries spanned the globe — from US companies that import raw materials to an Australian apparel company. “There are a lot of questions coming in from companies,” she said.

Among those looking for answers are Kim Osgood and Mike Roach, who own Paloma Clothing, a women’s clothing store in Portland, Oregon. The shop offers products that include jewelry, accessories, sweaters, scarves and rain coats. The store has already begun placing extra orders from its vendors who manufacture overseas.

“The one thing as a business owner that you absolutely abhor is uncertainty,” Roach says. “But there’s not a lot we can do.”

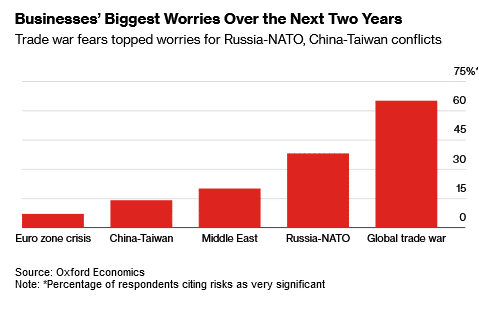

Such paralysis appears to stem from fear. According to an Oxford Economics survey of 156 businesses in the two weeks to Dec. 10, 65% of respondents said a global trade war presents a very significant risk to the global economy over the next two years, compared with 38% for a Russia-NATO showdown and 14% for a China-Taiwan conflict.

Across China’s vast manufacturing hubs, businesses are trying to maintain export sales. In Hangzhou, about 90% of Hangzhou Skytech Outdoor’s products are exported to the US, making it vulnerable to tariffs in excess of the 25% already slapped on its American exports during the first trade war in 2018-19.

The firm is considering offering its US buyers a price that incorporates both tariffs and freight, but those would need to be at least 10% to 15% higher, Hu said, depending on the new tariff level. In the meantime, the company is aiming to ship half of 2025’s expected demand before Trump is sworn in.

About three weeks after the election, when Bloomberg News reporters visited, the workshop and warehouse were piled high with boxes on pallets ready to ship as workers hurried to bend and cut metal to meet the peak demand season. After a boom in sales during the pandemic the firm decided to expand — it’s currently building a new five-story workshop and showroom which would double capacity.

Crossing the muddy construction site, Sunny’s husband, the CEO of the company, looked at the almost-finished building and noted all the uncertainty the company faces.

The unknowns are equally vexing at Carlsbad, California-based JLab. Its products were hit by tariffs in 2019 during the first Trump administration after requests for exclusions from the duties were denied. That prompted Cramer to move about 90% of his contract manufacturing from China to Vietnam, Malaysia and other countries. “We were essentially forced to rebuild our supply chain outside of China, and that’s not an easy thing to do,” he said.

Cramer said trying to build up inventories before tariffs are imposed isn’t really practical because that takes cash and with ever-changing technology, he could be stuck with obsolete inventory. And Trump might do something other than what he said he would during the campaign.

While the company didn’t raise prices after tariffs were enacted in the first Trump administration, that may not be possible this time. His top-selling product is a $24.95 wireless ear bud, and while he can absorb some additional cost from the tariff, he’ll have no choice but to pass on some of it because of his low profit margins.

“We’re designed to offer a fair product at a fair price, and when tariffs come into play, that makes it harder to do,” he said.

Many businesses that adjusted to Trump’s first round of tariffs would struggle to deal with a second blow, according to Evelyn Suarez, a customs attorney based in Washington whose clients include US manufacturing companies that import parts and components from China. “They’re at the level they could manage, but if you add on another 60% — that would be prohibitive.”

Suarez said her clients are “bracing for higher costs and that’s a real challenge because prices are going to go up.”

Arnold, with winemaker Weingut Jul. Ferd. Kimich, had to absorb about 80% of Trump’s tariffs during his first presidency to keep customers who could otherwise pivot to less expensive wines from other regions. Both Arnold and the US importer he works with want to maintain relatively steady prices for customers this time around too; the question is how the additional cost of the tariffs will be split between them.

Arnold, who exports about 10,000 bottles of wine to the US each year amounting to about 5% of his overall volume, said he’s confident he can wait out another round of tariffs, though higher-margin markets like Scandinavia start to become more attractive export destinations if the tariffs are in place longer term. Some German winemakers, however, sell as much as 40% of their product to the US. For them it will be tough, he said.

“This time the tariffs could come fast and last much longer,” Arnold worries.

Read the full article HERE.