Rising rates would be bad news for bondholders and borrowers of all stripes, particularly the U.S. government. They cast a shadow over stocks, too.

For both bondholders and borrowers, the pain of higher interest rates may have only begun.

President Donald Trump will have to decide if he wants to be part of the problem—or part of the solution. Many of the political promises that got him elected, including tariffs, tax cuts, and heavy government spending, could push interest rates higher.

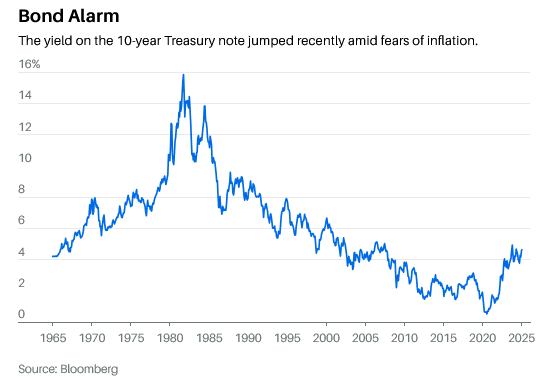

The bond market has gone through one of its most wrenching periods in history, capped by plummeting prices late last year and in early January. For investors, the rise in yields from an unprecedented zero percent to near 5% has meant the worst fixed-income returns in almost 90 years.

Housing has suffered a double whammy as new homes have become unaffordable for many buyers facing 7% interest rates on mortgages, which take their cue from bonds. And prospective sellers are frozen in place rather than trading their old 3% loans for much costlier ones.

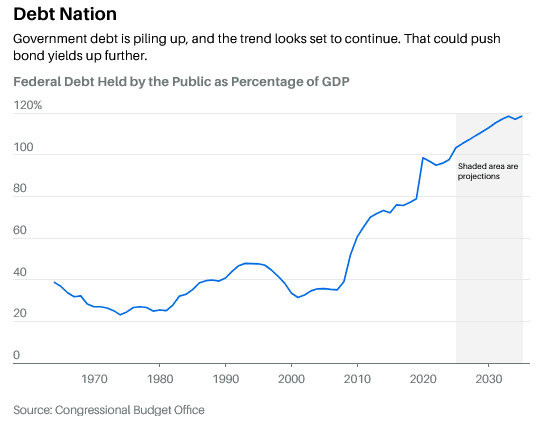

The U.S. Treasury, the world’s biggest borrower, has felt the pressure of higher bond yields most acutely. After running budget deficits previously only seen during wars or recessions, the U.S. government’s total debt has grown larger than the U.S. economy. When it could borrow at rates under 1%, this debt appeared manageable. At current borrowing costs, the government’s interest tab is the fastest-growing part of its budget, surpassing defense expenditures in 2024.

To bond investors, who are Uncle Sam’s lenders, this burgeoning debt points to still higher interest yields and lower bond prices in the years ahead. That growth is driven by ongoing deficits totaling 6% of gross domestic product, which in turn are boosted by surging interest expense on existing and new debt.

High rates are hammering borrowers. Lower-quality companies, especially those that rely on bank loans and private credit, are seeing increased credit stress. Commercial real estate is in a tightening vise as old, low-cost loans have to be refinanced at higher rates while sectors such as office buildings remain depressed.

Then there’s the stock market. Equities will suffer if bond yields keep heading higher. Late last year and into early January, stocks stumbled as the yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury note shot up from 3.6% to 4.8%. Then equities rallied as the Treasury yield fell back by a quarter of a point on better-than-expected inflation news. The S&P 500 index hit another record this past week.

Interest rates are also front and center for President Trump. In a Thursday video address to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Trump said he would “demand that interest rates drop immediately,” in a public signal to the Federal Reserve.

The problem is that the bond market may not follow the central bank’s lead this time. When the Fed cut its federal-funds target by 100 basis points late last year, the 10-year Treasury yield did the exact opposite, rising to its recent peak.

Regardless of Trump’s dictates to the Fed, the bond market “is likely to price in more uncertainty because of the inherent contradictions among many of Trump’s policies, the volatility around their application (for example tariffs), and still-too-large budget deficits,” writes Steven Blitz, chief U.S. economist of TS Lombard.

Blitz thinks 10-year Treasury yields could climb to 6%, a level not seen since mid-2000. That is especially true if the Fed ends its rate cuts and lifts the fed-funds rate to 5% to 5.25% in two years, from the current target range of 4.25% to 4.5%.

A 6% Treasury yield could translate into a 7% yield on corporate bonds. “This yield level can be problematic for the equity market,” Blitz concludes. “Institutional equity market investors will likely reassess allocations, and 7% yields could accelerate the natural bias for a net outflow from the equity market among aging baby boomers.”

The current near-5% Treasury yields only look high compared with the 1.5% to 2.5% yields levels that prevailed in the decade following the financial crisis of 2008-09, notes Richard Sylla, who literally wrote the book on the subject, A History of Interest Rates.

One of the lessons of this history is that long-term interest-rate cycles typically run for 20 to 40 years, Sylla tells Barron’s. Yields bottomed around 0.3% during the Covid-19 market panic of March 2020, says Michael Hartnett, chief investment strategist at BofA Global Research. Although Hartnett predicts that bond and stock markets will rally later this year as the 10-year yield dips under 4%, he sees rising bond yields as the No. 1 long-term risk faced by investors.

Until the post-Covid updraft, yields had been tumbling. Interest rates fell over four decades, starting in 1980, with staunchly anti-inflationary monetary policies, smaller government and deregulation, and broad globalization that saw the fall of the Soviet Union, China’s emergence in the world economy, and the North American Free Trade Agreement, or Nafta, Hartnett says.

After the financial crisis, that free-market orthodoxy was flipped, with interventionist fiscal and monetary policies. Central banks drove policy rates to zero (or below, in Europe and Japan), which was augmented by massive purchases of bonds to inject liquidity, known as quantitative easing. That bond buying accommodated deficit spending by governments while lifting asset prices.

At the same time, Hartnett says, populism took hold internationally, culminating with Donald Trump’s first presidential victory in 2016 and his reelection last year. Fiscal policies turned to “extreme excess,” with the U.S. budget deficit exceeding 6% of GDP in fiscal 2024. At $36 trillion, the national debt exceeds the size of the U.S. economy.

All this makes one wonder whatever happened to the “bond vigilantes” of a previous era, says Martin Barnes, a former chief economist at BCA Research. In the 1980s and 1990s, these bond investors would rebel when fiscal and monetary policies diverged from practices that had brought interest rates down from the stagflationary 1970s. They would drive bond prices down and yields up.

Some hint of the vigilantes came with the abnormal rise in bond yields after the Fed cut last year. Sylla sees that as reaction to easing monetary policy while inflation still ran close to 3%, above the central bank’s 2% target.

Eventually, Barnes expects bond vigilantes to return, forcing the government to pay a fiscal risk premium. It’s unknown when they will exact that price. He notes that economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff posited after the financial crisis that a debt-to-GDP ratio of 90% would cause economic problems. Yet U.S. total government debt exceeds 120% of GDP and hasn’t set off alarm bells.

Hartnett thinks the new administration could surprise with its spending curbs. He sees both a “devilish Trump and an angelic Trump,” with the latter slowing the deficit’s path.

Treasury Secretary-designate Scott Bessent has set an ambitious “3-3-3” plan, consisting of halving the deficit to 3% of GDP, real economic growth of 3% annually, and boosting U.S. domestic oil production by three million barrels a day. But BTIG Washington analyst Isaac Boltansky is skeptical, saying “deficit hawks are the most endangered species in Washington.”

The Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, led by Elon Musk is unlikely to make a dent in the deficit. Consider that in 2024 almost 60% of the $6.75 trillion in federal spending went for Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security; while 13% went for interest on the national debt, and about the same amount for defense expenditures. Discretionary nondefense spending, the likely target for cuts, accounted for only 13% of expenditures.

The Congressional Budget Office projects the deficit to total 6.2% of GDP in 2025, shrink to 5.2% by 2027, then climb again to 6.1% by 2033. “Since the Great Depression, deficits have exceeded that level only during and shortly after World War II, the 2007-09 financial crisis, and the coronavirus pandemic,” the CBO said.

The CBO’s outlook embodies optimistic assumptions. It assumes no recessions in the coming decade. It is based on current law, notably the expiration of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, the signature tax measure of the first Trump administration. Renewal of the tax law, a major objective of Trump’s, would add about another $4 trillion to the debt over the next decade. And that is before adding goodies like exempting tips and taxes from overtime pay, as he promised on the campaign trail. No one knows how much tariffs will offset the shortfall at this point.

Read the full article HERE.