The fundamental message is that we’re close to the limits of growth

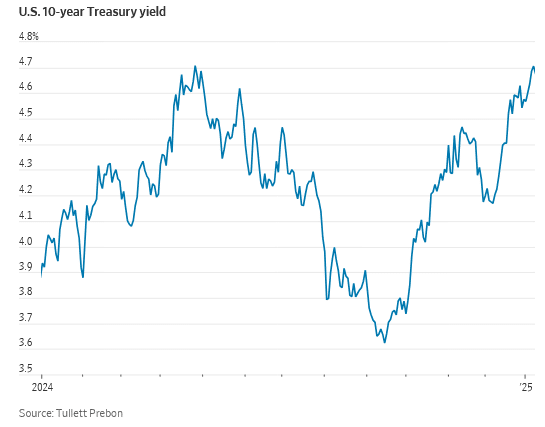

The 10-year bond yield came within a whisker of its high from last April on Wednesday morning, and stocks, especially smaller stocks, didn’t like it one bit.

It is part of a switcheroo by investors over the past month. They have shifted from thinking that higher Treasury yields are just an unwelcome side effect of the stronger growth promised by president-elect Donald Trump, to worrying that higher borrowing costs might end up being very important. If the concern is right, get ready for a bumpy ride in 2025.

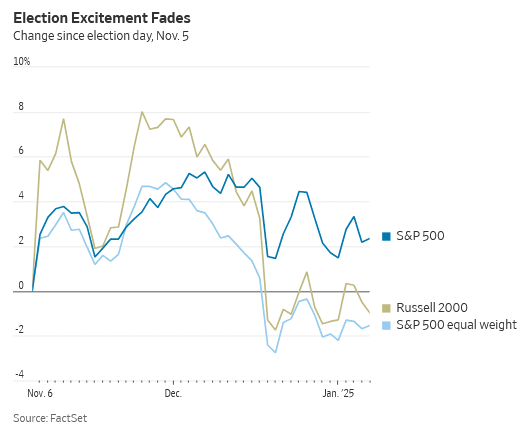

The story really starts with the excitement in the run up to, and shortly after, the election. Stocks and bond yields both soared, as investors anticipated a ton of good stuff from a new Trump administration: deregulation and lower taxes to boost growth and tariffs to extract concessions from other countries. Higher bond yields didn’t matter with so much good stuff to dream about.

It took only a few weeks for reality to kick in. Trump might not do only the good stuff, with promised deportations and permanent, rather than negotiable, tariffs pushing growth down and inflation up.

Just as bad, the risk is growing that the economy can’t cope with much of the good stuff. When the economy grows faster than is sustainable the result is either inflation or higher interest rates, or both. Bond yields rose in anticipation.

By Christmas smaller stocks and the equal-weighted version of the S&P 500—which treats pipsqueaks the same as the Big Tech stocks that dominate the normal index—were both below pre-election levels. Meanwhile Treasury yields leapt, on their way to the 4.7% they hit this week.

The big question: Did stocks suffer because bond yields are so high, or merely because they rose very fast in a short space of time? If it is the level of yields that matters, equity markets have a problem. If it is the pace of change, the drop in stocks is merely a matter of indigestion and investors can wait it out.

I think stocks are suffering because of the fundamental message from bonds, not the speed of change. But it is true these are hard to tease apart.

The fundamental message is that we’re close to the limits of growth. Instead of making everyone better off, when the economy runs too hot, it merely generates inflation, and the Federal Reserve has to cool it down with higher interest rates. To be clear, we’re not there yet: Futures traders still price in one Fed cut this year as the most likely outcome. But they think there is only a 16% chance of more than two cuts, while in early December that was seen as more likely than not. More fund managers predict no cuts this year.

Making things worse for stocks, there is also a supply problem. If the Trump Treasury shifts away from Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s focus on shorter-term borrowing, more bonds will have to be issued, even if the deficit doesn’t rise. Companies have been borrowing heavily, too, as they refinance maturing pandemic-era debt.

Higher yields caused by stronger growth are usually fine for stocks, because stronger growth means higher profit. But higher yields without more growth just mean pain.

Iain Stealey, international CIO for fixed income at J.P. Morgan Asset Management, said bonds are starting to look attractive both for their yield and their protective qualities in a downturn. That is despite stickier-than-expected inflation and possible inflationary policies from the new administration. But he hasn’t loaded up on bonds yet. Yields might still rise further. “The momentum definitely feels toward higher yields in the near term,” he said.

If yields keep rising, stocks could have a big drop, as they did when yields jumped toward 5% in October 2023. “When does it start to bite?” asked Guy Miller, chief market strategist at Zurich Insurance Group. “I suspect it’s a bit higher than where we are today, maybe another 50bp [half a percentage point] on 10-year yields.”

Investors who, like me, worry about high valuations and investors crowded into hot stocks might want to buy bonds now. Sure, higher near-term yields would bring immediate losses. But as Christian Mueller-Glissmann, head of Goldman Sachs’s asset allocation research, points out, even the price losses from a rise to a 5% yield on a bond bought today would be covered by less than six months of income from the bonds.

Investors who stick to stocks should have their fingers crossed that yields ease off again.

Read the full article HERE.