Governments are buying up gold as they see it as a safe investment – and, in some cases, a tool for evading Western sanctions

Gold prices have surged this year as investors seek safe investments amid a spike in economic uncertainty unleashed by US President Donald Trump’s tariff policies.

But economists say that there is another important factor driving the rally: purchases by central banks.

In this explainer, we explore why central banks are increasingly turning to gold assets, how that is driving a long-term structural shift in demand for the metal, and what that means for gold prices going forward.

Why are central banks buying up more gold?

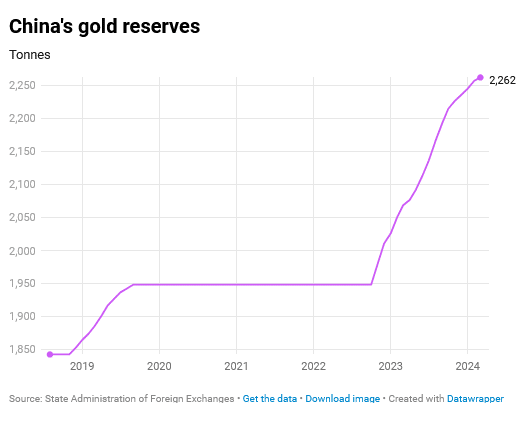

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and the wave of Russian asset freezes by Western countries that followed “marked a turning point” for the way central banks viewed gold, according to a report by Goldman Sachs Research.

Central banks’ purchases of gold have increased fivefold since the invasion began, and demand from governments is expected to remain high for some time to come, giving gold prices an “ongoing boost”, the report said.

Countries are increasingly experimenting with creating gold-backed digital assets and trading systems that bypass the dollar-denominated financial system, according to an article by Kimberly Donovan and Maia Nikoladze of the Atlantic Council’s Economic Statecraft Initiative published earlier this month.

“In many cases, these initiatives are for purely economic benefits,” the article said. “However, gold is also being used by US adversaries to evade sanctions or finance activities that counter US national security interests.”

What are central banks’ gold asset positions now?

The global average is roughly 20 per cent, but there is a divergence between developed markets and emerging markets, according to Goldman Sachs.

Developed markets tend to have larger gold holdings – partly as a legacy of the gold standard era when sovereign money supplies were linked to the commodity – that leave them with a higher proportion of their reserve assets in gold.

For example, central banks in the United States, Germany, Italy and France hold more than 70 per cent of their reserves in gold, as of the first quarter of 2025.

China, on the other hand, holds about 5 per cent of its reserves in gold, as foreign currencies comprise a higher proportion of emerging markets’ central bank holdings, according to Goldman Sachs.

Japan’s holdings of gold are at about 6 per cent.

Goldman Sachs views the global average of about 20 per cent as a plausible medium-term target for large emerging central banks.

What is the outlook for gold?

Joni Teves, a precious metals strategist at UBS, said on May 15 that gold prices could reach US$3,500 per troy ounce this year in an “upside scenario”. The bank expects the gold rally to extend into next year and for prices to stabilise at higher levels further out.

“The case for adding gold allocations has become more compelling than ever in this environment of escalating tariff uncertainty, weaker growth, higher inflation and lingering geopolitical risks,” Teves said.

“The current backdrop wherein global trade, economic and geopolitical relationships may be changing reinforces the need to diversify into safer havens like gold,” she added.

Goldman Sachs predicts that gold will rise to US$3,700 a troy ounce by the end of 2025 due to “renewed appetite” from investors and a long-term structural shift in demand from central banks.

Meanwhile, exchange-traded funds (ETF) are also beginning to join the gold rally.

State Street Global Advisors said in a report issued in May that global gold ETF physical holdings are still down 18 to 20 per cent from the 2020 pandemic peak, which indicated that there is “plenty of scope” for investors to “re-engage” in buying gold as they assess the macro market conditions in the second half.

Read the full article HERE.