The Federal Reserve’s next move on interest-rate policy depends on the Trump administration’s next move—or series of moves—on trade policy.

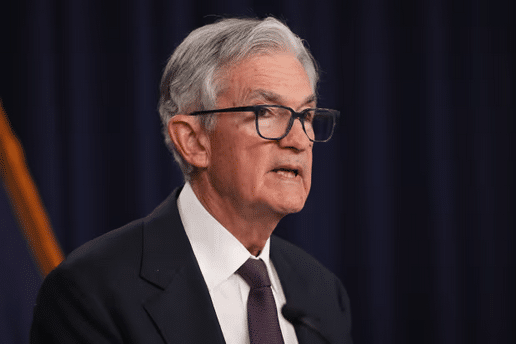

In a statement released Wednesday after the Fed’s May policy meeting, and in Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s comments at a postmeeting press conference, the message was clear: President Donald Trump’s sweeping tariffs have clouded the central bank’s economic outlook, making it nearly impossible to forecast whether inflation or unemployment will prove to be the more urgent threat.

The scale of the White House’s “Liberation Day” tariffs “was significantly larger than anticipated,” Powell said.

That leaves the Fed, which held the federal-funds rate target range steady at 4.25%-4.50%, in wait-and-see mode, so much so that Powell referenced “waiting” more than 20 times during a nearly hourlong press conference. Rick Rieder, chief investment officer of global fixed income at BlackRock, called the Fed’s stance “assertive inaction” in a client note.

The Fed’s dual mandate stipulates that it must foster price stability and full employment. Yet, as the FOMC statement stated, and as Powell’s comments later reinforced, Fed officials judged that “the risks of higher unemployment and higher inflation have risen,” largely due to uncertainty surrounding tariffs.

The economy remains solid enough to justify patience with regard to any monetary policy changes, Powell said, while emphasizing that the cost of waiting to make changes is relatively low. The Fed, Powell said, is in a “good place” to wait and see what happens.

By Thursday morning, futures traders were pricing in about 17% odds of a quarter-percentage-point cut in the fed-funds rate at the June policy meeting, down from 30.5% on Tuesday and 63% a week ago, based on the CME FedWatch tool.

The market’s attention has now shifted to the policy meeting ending July 30. Odds of a rate cut of the same magnitude at that meeting were 59% late Wednesday, up from 35% a week ago.

Much will depend on the scope and duration of tariffs, and whether they result in a one-time bump in prices or more persistent inflation, none of which is clear right now, Powell said. That’s a change in tone from the Fed’s messaging after the March meeting, when officials emphasized the transitory nature of trade policy-induced price hikes.

“We’re going to need to see how this evolves,” Powell said on Wednesday.

Not everyone agrees with the Fed’s current posture. Neil Dutta, head of economics at Renaissance Macro Research, said in a note that Powell’s labor-market views were outdated.

“Powell’s views on unemployment seem very stale, in my view,” he wrote on Wednesday. “Labor market conditions are said to be solid even though labor demand continues to cool, hiring rates are low, and average hourly earnings have slowed. What makes the Fed assume this stabilizes on its own? It can’t and won’t, which means a policy response will ultimately be required.”

In recent months, the unemployment rate has been “moving sideways,” but at 4.2% it is still within the range of maximum unemployment, Powell said.

Powell conceded that a wait-and-see policy means the Fed won’t be able to take pre-emptive action ahead of a potential economic slowdown. “It’s not a situation where we can be pre-emptive because we actually don’t know what the right response to the data will be until we see more data,” he said.

Powell also pushed back at the press conference on recent political and public criticism of the Fed. In response to a question, he said Trump’s public pressure to cut interest rates “doesn’t affect our doing our job at all.”

He added, “We’re always going to only consider economic data, the outlook, and the balance of risks. That’s it.”

Although previous presidents have routinely met with Fed chairs, he confirmed that Trump hasn’t requested a meeting during this presidential term. “I’ve never asked for a meeting and I never will,” Powell said. “It always comes the other way.”

Powell also responded to recent criticism from former Fed Gov. Kevin Warsh, who is widely believed to be Trump’s next pick for Fed head. In a keynote speech last month, Warsh accused the central bank of mission creep and overreach.

“We did things on an emergency footing during the pandemic,” said Powell. “We knew we wouldn’t get everything perfect.”

He acknowledged that the Fed could have done a better job explaining quantitative easing, its strategy of buying assets such as government debt to increase financial-system liquidity, but defended the central bank’s independence and scope.

On climate-related efforts, the Fed’s role is “very, very narrow,” he said, adding that suggestions to the contrary are exaggerated.

The main message of the Fed’s May meeting, however, was pervasive economic uncertainty, and the central bank’s decision to stay the course, watch, and wait.

Read the full article HERE.