President-elect plans tariffs and tax cuts, as in his first term. There are risks with both, but also lots of caveats.

Key Points

- Trump’s second-term economic agenda includes higher tariffs and lower taxes, potentially leading to higher inflation and interest rates.

- Tariffs could pose a greater inflation risk than in Trump’s first term.

- Tax cuts may provide a temporary economic boost but could also increase the deficit and put upward pressure on interest rates.

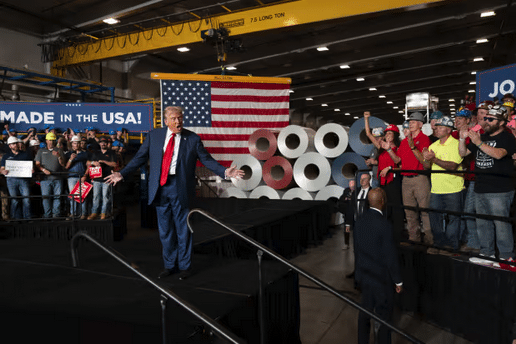

Voters have re-elected Donald Trump in great part out of dissatisfaction with the economy under President Biden and nostalgia for the low inflation and prepandemic conditions of the former president’s first term.

To fulfill those voters’ hopes, Trump’s main economic tools will be the same as in that first term: tariffs and tax cuts. But there’s a difference. The tariffs he’s planning will be broader and higher, and the tax cuts more narrowly targeted.

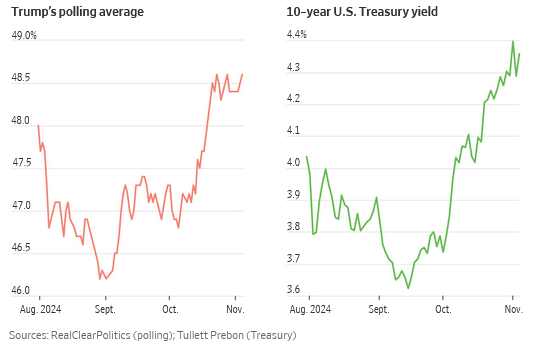

The consensus of economists and investors is that tariffs will put upward pressure on inflation while tax cuts could spur growth and add to deficits, together tending to nudge interest rates higher. And indeed, long-term Treasury bond yields had risen recently on strong economic data and Trump’s improved polling, and shot up early Wednesday, along with stock-index futures, as Trump’s victory became apparent.

The first years of Trump’s first term were better for the economy than many expected on election night in 2016, and expectations could be similarly miscalibrated now. For one thing, he inherits a relatively benign outlook. Growth has been surprisingly strong while inflation has fallen substantially from its peaks, although prices are still high. The Federal Reserve is set to trim interest rates Thursday for the second time this year. This should keep recession risks to a minimum.

As for Trump’s own plans, he may not raise tariffs as much as threatened, opting for negotiations over trade war. Congress may water down his tax plans. Finally, presidents are seldom the main driver of economic performance. Trump’s policies may have less to do with how the economy performs over the next four years than larger forces and unexpected events, such as a crisis, a war or a boom driven by new technology.

Trade comes first

His first opportunity to make a mark will likely be on tariffs, where he can act without asking Congress’s permission. Even so, administrative procedures and negotiations could delay implementation. In his first term, 11 months elapsed between initiation of the case against China and imposition of tariffs. Tariffs may also be rolled into broader negotiations on extending the 2017 tax cut.

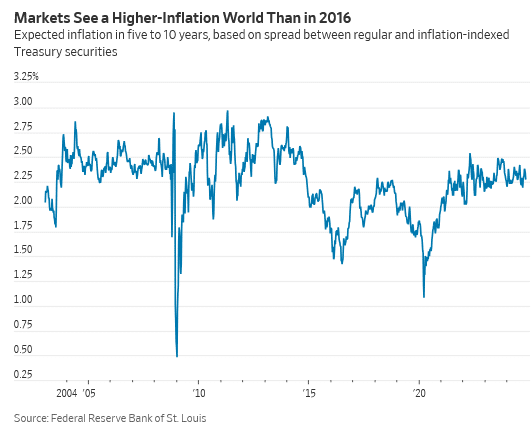

Trump’s first-term tariffs had no noticeable effect on inflation because they were relatively modest, and globally subdued demand and investment and slack labor markets were pushing in the opposite direction. On the eve of his election, wages were rising just 2.4% a year. Bond investors expected future inflation to average 1.8%, below the Fed’s 2% target.

This time Trump has proposed much higher tariffs—at least 60% on China, and 10% to 20% on everyone else. Such a combination would lift U.S. tariff rates to their highest since the 1930s. And it would come when demand is brisk, supply chains are vulnerable to geopolitical conflict, and memories of inflation are fresh. Wages are growing 3.8% a year, and bonds see future inflation at 2.3%.

This suggests tariffs could pose more of an inflation risk than in his first term. Morgan Stanley estimates Trump’s 60% and 10% plan would raise U.S. consumer prices 0.9%. That’s a one-off effect: Eventually, inflation should fall back to its underlying trend.

But other factors could result in a smaller impact. Importers could absorb more of the tariff into their margins. The dollar could rise, offsetting higher import prices. Most important, some advisers say Trump is using tariffs as a negotiating tactic to lower other countries’ trade barriers, so actual tariff increases will be less than he has threatened. And if Trump sees tariff fears hurting stocks or pushing up interest rates, he may compromise.

Goldman Sachs economists think Trump would raise tariffs on China by 20, not 60, percentage points, and will not impose an across-the-board tariff on other countries. In that scenario they think inflation excluding food and energy, using the Fed’s preferred price index, would fall from 2.7% now to 2.3% in a year, instead of 2% in their baseline forecast. That difference won’t stop the Fed from cutting interest rates, they conclude. Inflation at that level would still be lower than for most of the past three years.

Then come taxes

Portions of the tax law that Trump and congressional Republicans passed in 2017, such as for lower rates for individuals and businesses who pay their taxes on their individual returns, expire at the end of 2025 and they have given priority to extending the law. That would cost about $5 trillion over 10 years, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimates. The process is likely to consume a lot of next year.

Full extension shouldn’t have much effect on growth or interest rates because that’s already built into the behavior of investors and the public.

Not so with Trump’s other proposals, which have at times included lower corporate tax rates; exempting tips, Social Security benefits and overtime pay from taxes; and deductions for car loan interest and state and local taxes. These proposals would, the CRFB estimates, add about $4 trillion to the deficit over 10 years.

Tariff revenue would reduce that cost somewhat as would spending cuts, though Trump also plans some spending increases.

The 2017 tax law was good for long-term growth because it simplified the tax system by lowering rates on income, profits and investment and narrowing tax breaks, said Kyle Pomerleau, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute. Trump’s new proposals won’t have the same benefit because they add back complexity via new tax breaks, he said.

Still, lower taxes should provide some boost. Deutsche Bank estimates that a unified Republican government would boost growth by 0.5 percentage point in 2025 and 0.4 in 2026 without higher tariffs. With a 60% tariff on China and 10% on everyone else, Deutsche estimates the net effect on growth becomes negative.

Tax cuts would also add to the deficit and put upward pressure on interest rates. John Barry, rates strategist at JP Morgan, estimates Treasury’s current schedule of debt auctions is enough to fund next year’s deficit, but would fall $3.3 trillion short from 2026 through 2029, without extension of the 2017 tax cut. The shortfall would be even larger if the tax cut is extended and Trump’s plans are enacted.

If the Treasury starts upping auction sizes to finance larger deficits, that is likely to put upward pressure on yields. Barry estimates a unified Republican government would raise 10-year yields by 0.4 percentage point, of which the market had already built in 0.15 point through Friday.

But with the last fiscal year’s budget deficit at $1.8 trillion, triple the level of eight years earlier, even a Republican Congress may not give Trump all he wants.

“A Republican Congress is not going to bend over backward to exempt Social Security benefits or overtime pay from tax, both on the merits of those ideas, and the cost,” said Don Schneider, a former Republican congressional aide now at Piper Sandler. “There simply are not the votes to do that.”

Still, Trump’s sway over Republican legislators has grown since his first term, and he has shown he can muscle through his priorities.

Regulations

Trump has proposed lighter regulation, for example of mergers and of the oil-and-gas industry. These ought to boost growth and business confidence and hold down inflation. But economists think the effects are too difficult to identify in the broader economy. For example, U.S. oil production and gasoline prices are driven mostly by global prices, which are in turn heavily influenced by OPEC, sanctions, Middle East conflict and Chinese economic growth.

Similarly, while Trump’s plan to deport unauthorized migrants could, at the margin, raise wage and price pressure, the impact may not be noticeable given the size of the U.S. labor market.

Trump’s economic agenda isn’t just about growth but also trying to restore the good jobs and healthy communities manufacturing once made possible while reducing dependence on China, a geopolitical adversary. “Yes, there’s a cost. In many cases, I think it is worth it,” said Scott Paul, president of the Alliance for American Manufacturing.

“Globalization produces disruption, dislocation, and destruction,” Robert Lighthizer, who was trade ambassador in Trump’s first term and will likely return in some role in the second, wrote last year. “Conservatives by contrast seek to defend traditional values and institutions, preserve the social fabric, and ensure the conditions for families and communities to flourish.”

Unlike GDP or inflation, these benchmarks for a Trump economy defy easy measurement. They are no less important.

Read the full article HERE.