Various forces are fueling gold’s rise. We take a look at whether it makes sense to latch on to the rally.

Gold is glittering, although not necessarily for the reasons everyone is talking about.

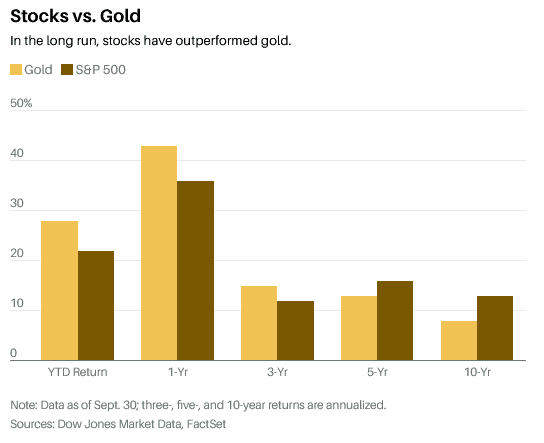

It’s rare for gold to beat stocks, but it’s doing so handily this year. The metal has hit no fewer than 40 record highs, the latest on Sept. 26, when it reached $2,695 an ounce. Prices got a lift after Iran attacked Israel. Its 28% year-to-date return beats the S&P 500.

Short-term trading is part of it. Hedge funds have piled in—collectively they are more bullish than at any time since at least the mid-1980s, according to an analysis of futures market data by Bespoke Investment Group. Some Wall Street firms expect more gains: Bank of America and Citigroup see gold at $3,000 next year, good for an 11% gain from recent prices.

But what’s really behind gold’s ascent? Everyone has a story: falling interest rates, central-bank buying, the rising deficit, or a hodgepodge of horribles like wars, pandemics, and erosion of the dollar’s purchasing power.

There’s truth in all of it, yet most of the stories explaining gold’s rise aren’t as strong as they appear. Gold has support, but it’s important to know what it is, especially if you want to add some to your portfolio.

Consider the interest-rate tale. The idea is that gold should rise as rates decline, which pushes down bond yields and makes bonds less appealing. Gold’s rise this year coincided with the market’s anticipation of rate cuts by the Federal Reserve, along with hopes for more cuts in the pipeline.

But there’s a muddled history of gold and interest rates: According to a 2021 study by researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, soaring inflation expectations from 1971-80 coincided with a surge in gold. The metal’s prices then fell in the early ’80s as inflation and rates started cooling.

In more recent history, gold has been inversely correlated to long-term “real” yields, adjusted for inflation. The idea is that if you own a “risk-free” Treasury bond, for instance, your inflation-adjusted yield will look less attractive as rates fall. That makes gold—and other tangible assets like real estate—more appealing. From 2001 to 2012, long-term real interest rates fell about four percentage points, accompanied by an “over fivefold rise in the real gold price,” the Fed researchers found.

Fund manager Pimco has estimated that a one percentage-point decline in real rates for 10-year Treasury notes should lead to a 24% increase in gold prices. Yet Pimco acknowledges that the relationship hasn’t held lately—gold rallied in the past two years when interest rates were higher. And the real yield on the 10-year Treasury is historically low at around 1.5%, leaving little room for more declines.

Other forces fueling gold’s rise include central banks. Led by China, India, Poland, and others, central banks bought more than 1,000 metric tons of gold in both 2022 and 2023, according to the World Gold Council. Central-bank buying has represented up to a quarter of global gold demand in recent years. Recently, however, purchases have begun to slow as prices crept up. China stopped buying gold in May. Overall, central-bank purchases amounted to just 183 metric tons in the second quarter, down 39% from 300 metric tons in the first quarter.

Gold still only represents 5% of China’s foreign currency reserves, leaving plenty of room for more large purchases. China and other large-scale buyers could become increasingly sensitive to gold prices. But if the dollar loses value as U.S. interest rates fall, central banks in China and other countries may pick up more gold as a reserve currency (though it would be more costly).

Gold bulls are pinning hopes on retail investors stepping up and buying through exchange-traded funds. Investors pulled more than $4 billion from these funds in 2023 as prices climbed, according to Morningstar data. Money continued to pour out during the first half of 2024, but fund flows turned positive in July.

“Gold ETF holdings are starting to increase,” says Imaru Casanova, portfolio manager of the VanEck International Investors Gold fund. “We see the re-emergence of Western investors as a very strong near-term catalyst.”

Longer term, gold bulls argue that the metal will hold up against the dollar or other currencies losing value. Granted, this is an ancient argument promoted by those who constantly worry about governments inflating away the value of their “fiat” currencies. And it doesn’t necessarily mean gold will beat other “real” assets like commodities or real estate. Stocks with cash flows and dividends would also be a hedge.

The idea, though, is that we’re entering dangerous fiscal territory: The U.S. debt has swelled to more than 120% of GDP, and neither Vice President Kamala Harris nor former President Donald Trump has spent much time talking about curbing the deficit or the country’s $35 trillion public debt.

In theory, the growing imbalance between tax receipts and spending will force the government to “print money,” leading to dollars losing value and prompting people to buy gold, due to its relatively fixed supply. (The same argument is made for Bitcoin as “digital gold.”)

Some advisors say that’s a good reason to buy. “It doesn’t matter who is running the government; they are both spending,” says Arnold Van Den Berg, founder of Austin, Texas–based registered investment advisor Century Management. The firm started adding gold to clients’ portfolios two to three years ago and now has it at 6% to 7% of most accounts, says Van Den Berg, who worries about inflation eroding the purchasing power of dollars.

“We’re not gold bugs. I bought gold in the 1970s, but we didn’t own it again until a few years ago,” he says. “We can’t predict what inflation is going to be but I have a pretty good sense history repeats itself.

Some fund managers like the geopolitical argument. Gold’s recent rally coincided with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. On Oct. 1, as Iran fired missiles at Israel, gold rose 1%. Pimco portfolio manager Greg Sharenow is bullish on gold, partly because geopolitical instability has increased. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine “was a fracturing of the world order,” he says.

What’s an ounce worth? Gold doesn’t have cash flows, so analysts try to peg prices to other commodities, demand from China, and factors like jewelry demand in India. Data analytics firm Quant Insight uses mathematical models to gauge which macroeconomic factors are driving prices; they conclude that gold today is most closely linked to copper—a proxy for Chinese growth. The firm says gold is more or less fairly valued, given today’s macro picture.

Other firms see gains ahead. Leuthold Group notes that gold historically does well after each rate cut in an easing cycle and actually gains momentum as the cycle progresses and the dollar weakens. “The rally looks a bit extended in the near term,” the firm said in a recent note, but “there is plenty of room for upside from a medium- to long-term perspective.”

There are a number of options for investors, including bullion, mining stocks, and gold ETFs.

Buying bullion holds a certain appeal, and has been a hit for Costco Wholesale: Members rush to snap up $2,689.99 single-ounce bars that quickly sell out. But apart from the hassles of storage, selling bullion may require a dealer who will charge a markup— sometimes as much as 5% to 10%.

Gold miner stocks present a different problem. While cheap and easy to trade, their share prices don’t always match gold’s price moves. That has been especially true over the past several years, when higher labor costs cut into profit margins. While gold prices have jumped 71% over the past five years, the VanEck Gold Miners ETF has returned 44%. Gold miners have leapt ahead over the past few months, but the mining industry’s ups and downs are an added variable.

That leaves ETFs like the $75 billion SPDR Gold Shares and the $32 billion iShares Gold Trust . These funds charge fees—0.4% for the SPDR fund and 0.25% for the iShares version—but they offer direct exposure to gold, and investors can buy and sell them cheaply and easily in a brokerage account.

How much to own depends on your appetite for insurance. Arnold’s approach is in line with some asset allocation research, which argues that gold can smooth your portfolio’s returns. Most advisors recommend keeping allocations below 15%.

Keep in mind that if gold keeps rallying, it may be for bad-news reasons. Pessimism about the economy’s future is usually positive for gold, according to academic research. Watch the University of Michigan surveys of consumer sentiment. Gloomier forecasts by consumers are good for gold and worse for stocks.

“Gold is the counterinvestment,” says Martin Murenbeeld, editor of Capitalight Research’s Gold Monitor. “Have a little in your portfolio and hope it doesn’t go up.”

Read the full article HERE.